Note: February is Black History Month.

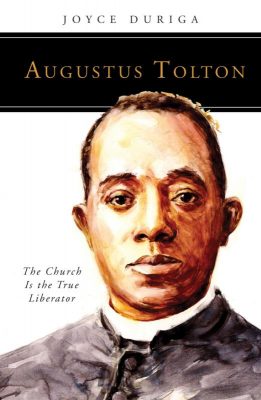

“Augustus Tolton: The Church Is the True Liberator” by Joyce Duriga. Liturgical Press (Collegeville, Minnesota, 2018). 128 pp., $14.95.

By Michael R. Heinlein

Although he died over 120 years ago, Father Augustus Tolton is a man for our times and his story deserves telling. It is the story of America’s first recognizably black Catholic priest and his faith, perseverance and holiness.

Joyce Duriga’s recent volume on his life for Liturgical Press’ “People of God” series is the latest contribution to the telling of his story.

Father Tolton’s story has spread in recent years, mostly due to the opening of the cause for his canonization in 2010. The late Cardinal Francis E. George stated in 2014 that introducing Father Tolton’s cause was “one of the most important, if not the most important” ecclesiastical actions he had taken in his nearly 17 years as archbishop of Chicago.

Telling Father Tolton’s story is no easy task. Much about his life is unknown. Records are especially poor because of his early status as a slave and as a man of color in a post-Civil War society. As research into Father Tolton’s life continues, more can be told. Much of what is known has been compiled in his official biography, called a “positio63,” which was submitted in 2018 to the Vatican Congregation for Saints’ Causes as part of the ongoing effort toward his canonization. Duriga’s work relies on this newest research to chronicle Father Tolton’s life.

The priest’s life, which began as a slave in eastern Missouri, is just as much harrowing as inspiring. Escaping for freedom with his mother and siblings, Father Tolton reached maturity in Quincy, Illinois, amid the inherent racism of postwar society. There he was forced to work arduous, low-level jobs instead of fulfilling his desire to study for the priesthood since no American seminary would accept him.

Alongside his labors, though, Father Tolton pursued many of the studies needed to prepare for seminary, useful when he was at last accepted to the Roman college that trained priests for foreign missions.

Duriga situates much of Father Tolton’s life within its historical context, including his first assignment as a priest — which likely took an unexpected turn of events because of a then-ongoing debate on race among American hierarchy.

The African missions to which he had been prepared to go would not be the place to test the mettle of Father Tolton’s holiness. Instead, he was assigned to his Quincy hometown, which became a crucible for the first identifiably black man to wear a priest’s cassock in America. He was maligned and mistreated by many — especially his own brother priests. In Father Tolton, though, like the scourged Christ, none of the hatred shown toward him was ever reciprocated. Rather, it was transformed by love.

Eventually, Father Tolton requested a transfer to Chicago, not so much to make his life easier as to allow his ministry to be more effective. A growing population of black Catholics there became his new flock. His work to establish a parish for black Catholics in Chicago, combined with a good deal of travel for speaking engagements on the plight of his people, took a toll on the priest. Father Tolton collapsed on a street corner in record-breaking heat in July 1897, and died shortly thereafter.

He left a lasting legacy by which he is remembered as a believer who always trusted in God’s plans, never allowing the hardships and obstacles he faced to keep him from attaining holiness, and as a model priest who spent himself in service to his flock, never seeking personal gain.

Duriga’s work includes several chapters on a variety of figures that made up the fabric of Father Tolton’s life and times, giving a context of his own life’s situation. Among these figures is St. Katharine Drexel — the heiress-turned-foundress who helped fund, among other things, construction of Father Tolton’s parish for black Catholics in Chicago.

Additionally, Duriga’s work includes two appendices. One provides a timeline of Father Tolton’s life and times, and another gives a glimpse into some of the most recent activity regarding his cause of canonization.

Duriga’s short and straightforward look at Father Tolton’s life is for a wide-ranging audience who would like introduction to the priest’s life. Despite some factual errors (such as the wrong name of Chicago’s first bishop), conjecture and other editing issues, the book provides an accessible starting point for further reading for those who would like to know more about this remarkable man.

Michael R. Heinlein studied theology at the Catholic University of America. He is a frequent contributor to the publications of Our Sunday Visitor, and serves as editor of SimplyCatholic.com.