How has COVID-19 affected farmers in the St. Cloud Diocese?

While farmers are grateful to live in the country, “most are hurt badly by lower prices and the chaos in the processing and delivery of their particular products,” said Joe Borgerding, a member of St. Peter and Paul Parish in Elrosa for 64 years.

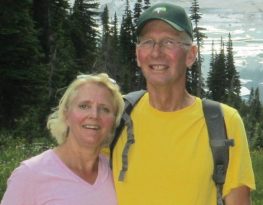

With his wife, Toni, and their family members, Borgerding farms the central Minnesota land he was raised on — a diverse organic grain and livestock farm. In response to the pandemic, the Borgerdings discontinued the noon meal they shared with employees. But the dilemmas they and other farmers face are about much more than distancing guidelines.

“Some have had to euthanize their pigs or birds, or dump their milk, after all the effort and expense of raising them,” Borgerding said. “So far, our co-op has processed and marketed all of our organic milk and meat, so we are fortunate.”

Disruption in the food system

Jim Ennis, executive director of Catholic Rural Life headquartered in St. Paul, described how fewer meals eaten away from home have created problems on the demand side.

“Our food system is so efficient that any disruption impacts everyone along the supply chain, from farmers and producers to distributors and food service operations,” Ennis said. “Food service sales represent half of all food purchased. Food producers have been hit with a decline in the demand for hogs, beef, poultry, milk and eggs.”

With that decline, food processing facilities struggle with large inventories.

“These facilities are efficient, but they can’t turn their operations on a dime,” Ennis continued. “They can’t quickly change packaging and sell to retail sectors, like grocery stores. Food service markets use different cuts of meat, different kinds and sizes of packaging.”

The disruptions affect hog farmers, Ennis said, who schedule their hogs to go to particular processing facilities during a particular time window for particular markets.

Anderson Farms in Belgrade is a diversified operation that includes hogs and cattle.

“I farm with my brother and my three sons,” said Jim Anderson, 67. “We produce 1,000 to 1,200 market-ready hogs each week in climate-controlled buildings. Half of our pigs are sold to food services.”

He feels fortunate for other sales outlets as well — for breeding stock and medical uses, like pigskins and livers used for skin grafts. As soon as his hogs reach market size, another group is ready to move into that space, he said.

“In most modern farms, hogs are bred a year before they are sold,” Anderson said. “At every step — farrow to finish — we provide the best environment and nutrition possible, and deliver to market what will be wonderful bacon and hams. But since the pandemic hit we receive about 60 percent of their normal value and lose $50 on every pig we sell.

“At grocery stores, pork loin used to be $1.50 per pound,” Anderson said. “Now it’s over three times higher. So people, especially poor people, can’t afford meat because prices have shot up.”

Even before the coronavirus, farmers operated on thin margins, Ennis explained. The pandemic has exacerbated the challenges they face in getting good prices for their products. Farmers can’t just keep on feeding their hogs, chickens and turkeys, because they get too big. But euthanizing animals is a painful conundrum for farmers.

“To destroy a beautiful healthy animal,” Anderson said, “that’s the biggest challenge of our lives. Euthanizing turns against every instinct you have.”

JoAnn Braegelman, rural life coordinator for the Social Concerns Office of Catholic Charities of the St. Cloud Diocese, owns a farm near Belgrade, which her son operates along with his farm.

“We’ve seen news reports of milk producers having to dump their milk,” said Braegelman, a member of St. Francis de Sales in Belgrade. “In Minnesota, we haven’t seen that, but it’s still chaotic and changing daily. Big portions of dairy markets have been disrupted. Milk producers have struggled with deflated markets during the last handful of years — many are selling at a loss already.”

“For example,” she said, “if farmers sold corn they planted today, factoring in expenses, where market prices are right now, they’d lose money. Unfortunately, no matter what commodity, with the market uncertainty, they could very well see a loss.”

Markets had dropped prior to COVID-19, Braegelman said. “Many farmers are operating at a net loss or are forced to sell their commodities at a loss, just to generate cash flow.”

Farming conditions often out of one’s control

“We face ‘pandemics’ every few years, where diseases can wipe out a whole group of pigs,” Anderson said. “In 1998, hog prices dropped to eight cents a pound. Another year, fire burned our barn and we lost 2,000 pigs. In the last 50 years, we’ve depopulated our pig barns five times because of hog diseases. In some ways, we’re used to it.”

To counter crises, Anderson Farms maintains high biosecurity with their pigs, he said. “We shower and change clothes before we ever enter barns and test to ensure the pigs’ health. Over the last 10 or 15 years, we’re better able to keep disease out of our buildings.”

Borgerding said, “We can only succeed with consumers that appreciate and afford what we produce. We are very likely to lose more farmers if we don’t have consumers to buy what we produce, which means they need jobs. People need farmers to continue producing the nutritional food that families now enjoy.”

“Farming requires a lot of faith,” Braegelman said, “for good weather, seed growth, healthy animals, good harvests, fair markets. But COVID-19 puts faith into a different category, with many unknowns. When markets plunge, smaller family-owned farms are hit the hardest, as they don’t have the assets of corporate farms.”

Some Minnesota crops require additional workers to plant and harvest, Ennis said. “The pandemic exacerbates finding qualified help where a shortage was already a concern. On larger dairy farms, people work close together. A safe working environment, keeping appropriate distances and following new protocols can be a challenge. At various meat-packing plants, workers are vulnerable doing their jobs in close quarters.”

Braegelman clarified. “Farmers can’t ‘close’ the farm, self-isolate or quarantine when crops have to go into the ground, animals need to be fed or cows need to be milked. They’re doing the best they can with COVID guidelines, but work comes first, so distancing guidelines may go on the back burner.”

“Farming is highly stressful already and COVID-19 adds even more stressors,” Braegelman said. “Farmers may be struggling to stay afloat, financially, emotionally and psychologically. It is vitally important that we act in solidarity and support rural life and the farmers who feed our country and our world. Farmers don’t often reach out for help when it comes to mental health, and with fewer mental health service providers in rural areas, travel becomes an obstacle as well.” (See information at the bottom of this story.)

The role of faith

Faith communities are important in supporting their farmers, Ennis said. Besides livestreamed Masses and online prayer services, priests and pastors meet all kinds of needs.

“I feel my beliefs align with what we do every day,” Borgerding said. “It’s a vocation, working with family in our greater community. I feel privileged to serve by producing nourishment for others, while providing a good life for my family. It’s an honor to care for a small corner of God’s creation. It’s humbling, after all these years of farming, to know that while I may plant straight, or timely, I cannot make the seeds grow by myself without help from above. That is the same help we need to call on to get through this trial.”

“Every morning when I wake up,” Anderson said, “I’m thankful for another day, thankful that we can do our jobs as farmers. There are always challenges. We can’t live in fear and run a normal farming business. No matter what happens, God is looking over you.”

RESOURCES FOR MENTAL HEALTH

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

- Crisis Text Line: Text “MN” to 741741

- Minnesota Mobile Mental Health Crisis Line: **CRISIS (**274747)

- www.farmcounseling.org

- www.mda.state.mn.us/about/mnfarmerstress

WHAT YOU CAN DO

- Pray: Catholic Rural Life sponsored a virtual novena to St. Isidore, the patron saint of farmers, which ended in a virtual Mass May 15, the feast day of St. Isidore. The novena will remain on the website for many months at https://catholicrurallife.org/

- Educate yourself about the Farm Bill. Funds cover SNAP, WIC and other important programs. Advocate to legislators on behalf of farmers. Teach children where their food comes from.

- Buy local to help smaller farms.

- Reach out to a farmer to offer support and appreciation. Send them a card of thanks and encouragement.

- Post on social media in support of farmers.

- Make a yard sign in support of farmers.

Photo at top of story: Bigstockphoto.com