WASHINGTON (CNS) — A pair of well-worn shoes left in the desert at the U.S.-Mexico border is the last thing you’d expect to find in one of the most prized rooms of the Washington museum known as The Phillips Collection, a premier venue for modern American art as well as classic European expressionists such as Renoir and Matisse.

But there, in a transparent case, in a space that focuses the viewer on the work of Mark Rothko, celebrated as a 20th century American artist but one who was born in what later became Latvia, the small battered shoes are on display.

They’re next to an item that looks as if it belonged to a child — a piece of cloth embroidered with the image of a lion. A description explains the items were found in 2018 near the Arizona-Mexico border by members of the Undocumented Migration Project at the University of California at Los Angeles.

The items, likely left behind by a migrant heading north, made up part of the 100 multimedia pieces in the museum’s “The Warmth of Other Suns: Global Stories of Displacement” exhibit focused on those forced to leave their homelands. It is on display until Sept. 22.

“A lot of the works can be very heavy,” explained a museum guide Aug. 29 — and she wasn’t talking about the physical weight of the objects.

Much like the person to whom the embroidered item likely belonged, Rothko left his homeland as a child, barely 10 when he left the Russian Empire and headed with his mother to a new life in the United States, where they arrived in late 1913. They resettled with other family members who had arrived earlier in Portland, Oregon.

A large part of the exhibit focuses on the emotional toll as well as the dangers of such immigration journeys, and one experienced in modern times by a record 70.8 million around the world, fleeing war, persecution and conflict, according to 2018 statistics from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

One of the rooms in the exhibit, with a large-scale photograph of the sea covering a wall, and jeans and shirts strewn on the floor, reminds museum-goers of the stream of recent refugee drownings. The clothing installation, by artist Kader Attia, is titled “La Mer Morte” (The Dead Sea) and is reminiscent of the Italian island of Lampedusa, where Pope Francis in 2013 called attention to tragedies faced by those seeking refuge from conflicts in Africa to Europe

Audio of waves and video of the sea nearby make it hard to escape the reality of the risks that refugees have confronted: Die drowning while trying to reach safety or die in a different way at home.

The exhibit takes up three floors of the Phillips, which is filled with portraits of refugees who arrived from Europe to Ellis Island in the early 1900s, photos of modern-day refugees from places such as Eritrea, Iraq and Syria who set up a refugee camp torn down in Calais, France, in 2016, audio in various languages in which immigrants speak of their experiences as well as the indignities they or their children suffer in their adoptive countries.

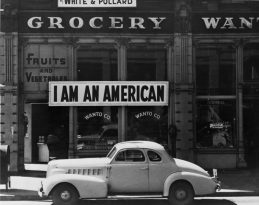

A black and white photograph of a building with a large sign that says “I am an American” showed what one American family of Japanese descent had to do the day after Pearl Harbor was attacked Dec. 7, 1941. Even after its prompt display of loyalty to the U.S., the family was sent to what was called a War Relocation Authority center, or an internment camp where some Japanese Americans were forced to live during World War II.

Though some of the items have a documentary quality, other art offers political commentary, such as the work of Siah Armajani, a Minnesotan artist, in a piece labeled with the ironic title “Seven Rooms of Hospitality.” It features plastic 3-D printed models of “uncertain spaces occupied by refugees, deportees, and exiles.” They include a cage, a shack and a model of a truck with the name of a company called Hyza on the side and the words describing its contents: “60 men, eight women, and three children, all dead.”

It was a reference to a 2015 incident in which 71 refugees and migrants from Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan suffocated in an airtight, refrigerated truck found abandoned on the side of an Austrian highway as they traveled from Hungary to Munich.

There’s also a chilling video made by Erkan Ozgen called “Wonderland” that focuses on a 13-year-old child who can’t speak, but miming with his hands and through grunts, describes an attack he witnessed and escaped from in his native Syria, motioning what seems to be a shooting and someone’s hands being tied. After watching, it’s hard not to hear his trauma through the grunts that travel through the museum floor.

Where a news item will document singular moments of difficulty, struggle, trauma and sometimes death that a displaced person may face, the exhibit’s photos, the audio playing in the background of migrants’ voices, videos of the empty and uninviting landscapes some of them have traveled through bring together the totality of the experience. Though it seems as if hope is absent and the “warmth” promised in the exhibit’s title is all but missing, perhaps it can be found in the space known as the “Rothko room,” where the migrant’s shoes are temporarily residing.

The Rothko room, a place where silence is encouraged, was envisioned as a place to meditate. Duncan Phillips, the museum’s founder, is said to have referred to it as a “chapel” and a painting by the immigrant artist, now widely recognized as a full-fledged American, hangs on each wall.

The paintings are of large and small blocks of bright and sometimes dark colors. According to the museum’s online literature, Phillips said of Rothko’s paintings that “what we recall are not memories but old emotions disturbed or resolved — some sense of well-being suddenly shadowed by a cloud — yellow ochres strangely suffused with a drift of gray prevailing over an ambience of rose or the fire diminishing into a glow of embers, or the light when the night descends.”

It’s hard to know how the journey of a displaced person will end, with success or with struggle, with the brightness of a new life like the one Rothko’s family was able to build or trudging through an unwelcoming place. The journey nevertheless began inside the shoes of a child that, like Rothko, was taken by his parents to start a new life in a new land.