By Tony Gutiérrez | Catholic News Service

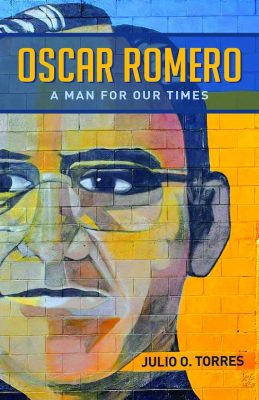

“Oscar Romero: A Man for Our Times” by Julio O. Torres. Seabury Press (New York, 2021). 208 pp., $19.95.

Rather than looking at what St. Oscar Romero can teach us, the Rev. Julio O. Torres co-opts the Salvadoran martyr’s legacy to push an agenda that is antithetical to the Catholic Church’s teaching on liberation theology. In the process, he also unnecessarily criticizes the church’s practice of celibacy.

Rev. Torres attempts to psychoanalyze St. Romero in what is known as a psychobiography to “shed light on the emotional forces that propelled individuals to act in response to their historical context.”

While one can admire the effort, his methodology seems a bit dubious. Much of his research included interviews with people who had known the archbishop, though he readily admits that people trusted him because he was a “padre.” Whether he made known he was an Episcopal priest and not a Catholic priest isn’t made clear.

In analyzing Archbishop Romero, he acknowledges the influence of Marxism on liberation theology and readily admits that “the thread of liberation theology … will inform this work also.”

Rather than taking a scholarly approach in analyzing the archbishop’s life, Rev. Torres falls victim to confirmation bias, where he has already predetermined the answers and is simply looking for the evidence to support it.

“Romero went so far as to condone the use of violence against the rich, even in such graphic ways as saying that they should take their rings off of their fingers and give them to the poor or else their hands would be cut off,” he writes, taking one of the saint’s homilies out of context.

The archbishop’s actual words were a plea to avoid a civil war rather than encouraging violence against the rich: “I appeal to you to listen to the voice of God and to share gladly with everyone your power and your wealth instead of provoking a civil war that will drown us all in blood. There is still time for you to take off your rings so that they aren’t removed from your hands by others.”

While he actively condemned violence and stood for the poor, St. Oscar was not calling for some kind of Marxist revolution. “Marxist political praxis can give rise to conflicts of conscience about the use of means and of methods not always in conformity with what the Gospel lays down as ethical for Christians,” he wrote in his Aug. 6, 1979, pastoral letter.

“The best way to defeat Marxism is to take seriously the preferential option for the poor,” he added.

Even Dominican Father Gustavo Gutiérrez, considered to be the “father of liberation theology,” has acknowledged that, while he admired Archbishop Romero, the latter was not an adherent.

Aside from Rev. Torres’ mischaracterization of Archbishop Romero’s view of liberation theology, he also goes into unnecessary speculation — without evidence — about the saint’s sexual behavior as a teenager. Even if this were the case, I don’t know of any other biographies that would contain such suggestions.

Rev. Torres, a married Episcopalian priest, says he was at one point a Catholic seminarian. It’s clear through his writing that he has a bone to pick with the church’s discipline of celibacy, and that this is one of the reasons for his becoming an Episcopalian.

“For Oscar, as for many, the church was the only way in which bright, sensitive and idealistic young men could find a way to obtain a good education, build a career and make a significant contribution to society — at the expense of vowing to forego sex altogether for the rest of their lives,” he writes, as if the very notion is unfathomable.

The one bright spot in the book is that Rev. Torres does go into St. Oscar’s very real struggles with self-doubt, anxiety and depression, referencing psychiatric evaluations that he voluntarily underwent, but noting that “none of the above implies moral failure.”

“To acknowledge Romero’s foibles and personal difficulties brings him closer to us as a model for emulation,” he writes. “It is not a matter of pathology vs. grace, but rather … God’s grace can and does act in us in spite of, and even through, our pathology.”

Unfortunately, even Archbishop Romero’s struggles with depression and anxiety are reduced to the church’s practice on celibacy: “Since he was a celibate, he was forbidden to be sexually intimate with another person who may have comforted and supported him. His loneliness may have constituted an additional source of frustration and depression.”

It is perfectly legitimate for someone of a different tradition to offer his perspective on St. Oscar and see what can be gleaned from his example. However, such works should always be respectful of the tradition from which the subject comes, which is where Rev. Torres has failed. Although he claims to admire St. Oscar, Rev. Torres has shown a disdain for the church Archbishop Romero loved, thus dishonoring his legacy.

Gutiérrez is a freelance journalist based in Cave Creek, Arizona, specializing in religion, and former editor of The Catholic Sun, official newspaper for the Catholic Diocese of Phoenix. He has bachelor’s degrees in history and journalism from the University of North Texas.