A Pastoral Letter by Bishop Donald J. Kettler

On December 8th, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception and the fiftieth anniversary of the closing of the Second Vatican Council, Pope Francis inaugurated the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy. His goal for the year is that Catholics across the world would “gaze even more attentively on mercy so that we may become a more effective sign of the Father’s action in our lives.” (1) The Holy Father highlights this goal by choosing as the motto for the year Jesus’ command to his disciples: “Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful” [Luke 6:36]. The mercy we have received, we are to give. We are called to focus on mercy in a special way during this Holy Year, not only so that we might understand and experience more deeply the mercy God has shown to us but also that we might practice it more generously in our dealings with others.

As pastor and teacher of the diocese, I offer this pastoral letter as part of our participation in this Holy Year of Mercy. It is inspired by the teachings of Pope Francis on mercy, especially Misericordiae Vultus in which he proclaims the Jubilee of Mercy and summarizes his theology of mercy. I encourage all to read and ponder this statement by our Holy Father. The current letter offers reflections of my own on mercy with a particular focus on what it means for our diocese. It is my hope that during this Holy Year parishes, schools, religious communities, and other offices or organizations of the diocese would discuss the revelation of God’s mercy in Scripture, our experience of that mercy, and how we can live it out in our diocese. This letter is intended to contribute to those discussions.

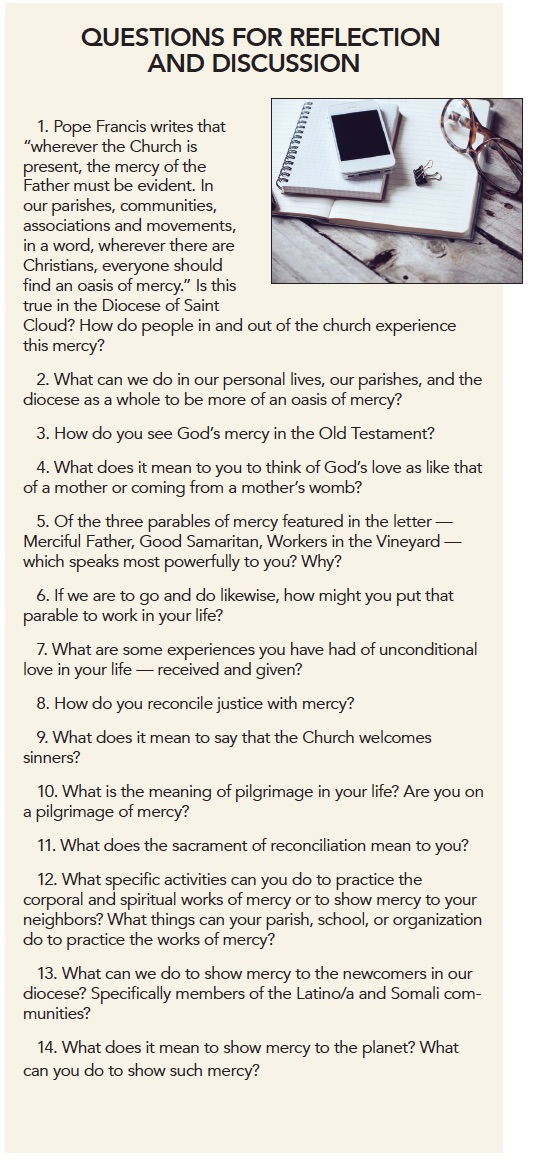

The Holy Father observes that “wherever the Church is present, the mercy of the Father must be evident. In our parishes, communities, associations and movements, in a word, wherever there are Christians, everyone should find an oasis of mercy” [MV, 12]. How and to what extent is this true in the Diocese of Saint Cloud? What are the signs of this oasis in our diocese? How do people in and out of the church experience this mercy? What can we do, individually and collectively, to make the diocese more of an oasis of mercy? What do we do or what can we do to manifest the mercy of God not only in our church activities but in our family, professional, and civic life?

I

POPES AND MERCY

The theme of mercy has been central to the papacy of Pope Francis. It is prominent in his preaching, teaching, informal comments in media like Twitter, and in his actions as pope. Things like washing the feet of prisoners, physically embracing those on the margins of society, or sponsoring refugee families witness powerfully to the mercy he calls us to ponder and practice in this Holy Year. While he has done much to elevate  it, especially with this Jubilee Year, the emergence of mercy as central to Christian life and teaching did not begin with Pope Francis. It was developed powerfully by each of the previous two popes.

it, especially with this Jubilee Year, the emergence of mercy as central to Christian life and teaching did not begin with Pope Francis. It was developed powerfully by each of the previous two popes.

Saint John Paul II makes it the topic of his second encyclical, Dives in Misericordia: On Divine Mercy (1980). He institutionalizes the importance of mercy by establishing the Sunday after Easter as Divine Mercy Sunday and making the first canonization of the new millennium Sister Faustina Kowalska who had a special devotion to divine mercy and a now-famous vision of the outpouring of mercy from Christ. During his last visit to Poland he dedicated the world to divine mercy and called the church to transmit the fire of this mercy to the world. Fittingly, he died on the eve of Divine Mercy Sunday in 2005.

Pope Benedict XVI continued this proclamation of mercy in his first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est: God is Love, in which he makes love, mercy, the center of his social teaching. He returns to this theme in his third encyclical, Caritas in Veritate: Charity in Truth, in which he identifies love or mercy as the normative principle not only for personal relationships such as family or friendships but also for social, economic and political relations.

Mercy was also a significant feature of the Second Vatican Council, a point Pope Francis emphasized in opening the Holy Door and the Jubilee Year on the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Council. Noting that “The Church feels a great need to keep this event alive,” the Holy Father went on to say that “With the Council, the Church entered a new phase of her history…. The walls which for too long had made the Church a kind of fortress were torn down and the time had come to proclaim the Gospel in a new way. It was a new phase of the evangelization that had existed from the beginning” [MV, 4]. He cited specifically the words of St. John XXIII on opening the Council as an indication of the path to follow: “Now the Bride of Christ wishes to use the medicine of mercy rather than taking up arms of severity.” In reading the signs of the times and discerning the call of the Holy Spirit, “The Church sensed a responsibility to be a living sign of the Father’s love in the world.” As Blessed Paul VI put it at the close of the Council: “We prefer to point out how charity has been the principal religious feature of this Council… the old story of the Good Samaritan has been the model of the spirituality of the Council” [MV, 4].

The centrality of mercy to Catholic teaching and our understanding of the work of the Church in the world has been a consistent and increasingly robust teaching of the Church in the last half century that is coming to fruition in a distinctive way in the Jubilee Year of Mercy.

II

A GOD OF MERCY

The ultimate source of our understanding of mercy is Scripture. At the center of the Bible’s revelation of God is the experience of God’s merciful love. We sometimes refer to the grand story from Genesis to the Book of Revelation as salvation history. Through this history God reveals himself to us; we come to know the character of God. What emerges as central to God’s character or nature is mercy. Indeed, what makes this a history of salvation rather than a history of judgment or condemnation is the mercy of God [MV, 7]. The theological tradition has tended to consider mercy as but one of God’s attributes alongside others such as eternal, all-powerful, and all-knowing. However, what becomes clear from God’s revelation of himself in Scripture is that mercy, love, is God’s essence. “God is love” [I John 4:8, 16].

OLD TESTAMENT

Before we consider some particulars of this revelation, it is important to address a common misunderstanding of how God is revealed in Scripture. It is sometimes said that the God of the Old Testament is a God of justice or even vengeance and the God of the New Testament a God of love or mercy. Not so. To be sure, there are texts in the Old Testament that can be cited in support of this view. However, by making those passages the key to interpreting all the others we fail to see how our understanding of God is progressively transformed through God’s dealing with Israel in the course of their history together. The God of creation and covenant; the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; of Moses, Ruth, and David; Isaiah, Hosea, and Esther is a God of mercy. It is this God and no other who is the Father of Jesus Christ. What we struggle to learn in both the Old and New Testaments is that God’s love, God’s mercy, is God’s defining characteristic. God’s anger passes but his mercy endures forever. God’s loving mercy is the key to understanding all the other texts. It is in service of this mercy that we must understand the judgment and even chastisement or punishment spoken of in both Old and New Testaments.

This mercy is present from the very beginning, for creation itself is an act of mercy. Scripture is clear and the tradition consistent in teaching that God creates not out of need but freely, as an act of bountiful love for all of creation. And as it came from the hand of God, the world was good, very good. This is the garden we were given in which to live, not because we earned it but simply because God loves us. As a further expression of this generous mercy, God even gives us dominion over “all the living things that move on the earth” [Gen 1:28].

But we were not satisfied. We disobeyed, wanting to be our own god. When we did, we were expelled from the garden. But God did not destroy or abandon us. He made clothes for us. After generations of increasing sinfulness, God calls Abraham into a covenant relation, which is later confirmed and elaborated with Moses. God articulates the essence of this covenant: “Ever present in your midst, I will be your God and you will be my people” [Lev 26:12]. The rabbis teach that the people of Israel were chosen not because they earned it by being special or great. Rather they are great because they are called by God. The call and the covenant are acts of mercy pure and simple. So too is the gift of the law which is given as a way to deepen the relation with God and show us how to live a good, faithful, blessed, even happy life.

The covenant at the heart of Scripture can be likened to a marriage. The history of Israel, like the history of each of us, is the story of God’s mercy in seeking out a loving relation with us. Sadly, it is also the story of our unfaithfulness in repeatedly breaking that covenant, betraying that love from the golden calf, through the kings and prophets, the crucifixion, right down to our own day.

The book of Hosea offers a particularly revelatory example of God’s mercy in the face of our infidelity. The people of God had again broken their covenant with God. As a result, God decided to show no more mercy to this unfaithful people [Hos 1:6], declaring that they shall no longer be his people [Hos 1:9]. The dramatic turn comes not in the form of repentance among the people, but when God remembers his love for Israel. God’s compassion rises and turns God’s own justice upside down. Instead of the people being changed, the change takes place in God who decides not to respond in anger or wrath, but with mercy: “I will not give vent to my blazing anger…; for I am God and no mortal, the Holy One present among you; I will not come in wrath” [Hos 11:9]. Thus, God reveals God’s self not as an angry and righteous God, but as a merciful God. This is the God of the Old Testament as well as the New.

In God’s patient mercy towards Israel, God shows what it is to be God. Despite the presence of sin, betrayal, and brokenness in the world, God does not react in anger but remains a God of unconditional love and acts according to his own loving kindness. God’s “goodness prevails over punishment and destruction” [MV, 6]. God’s love transcends everything mortal and every human calculation. God resists sin and injustice by refusing to react with wrath and instead continuing to love. In this bountiful mercy, God is true to himself. By being merciful, God does not allow the sin of the world to change his basic character or essence. God is free to be God, to be merciful.

The character of God’s mercy is further disclosed in three distinctive Hebrew terms often translated as “mercy:” hesed, hen, and rachamim. Hesed is used for the love between husband and wife [Gen. 20:13, Ruth 1:18] and the bond of deep friendship [1 Sam 20:8]. It suggests an on-going mutual relationship of care and affection, an unmerited loving kindness. Significantly it is used to express the covenant bond between God and Israel. When used of God, hesed conveys God’s free and gracious turning towards us with care. Hen has the sense of “grace” or “favor” and emphasizes the quality of mercy as a free gift, depending only on the good will of the giver, in this case, God. Rachamim comes from rechem which means “womb.” Here God’s mercy is likened to the powerful “womb-love” of a mother for her child that flows from the very center of one’s body and one’s being. Rachamim can also refer to intestines, which in the Hebrew understanding were considered the center of one’s feelings, as when we say we’re “going with our gut.” God’s mercy comes from the very center or essence of God. Mercy is that which is most true to God’s self, to God’s very being.

These terms come together in the words of God spoken to Moses on Sinai: “The Lord, a merciful [rachum] and gracious [henun] God, slow to anger and abounding in love [hesed] and fidelity” [Ex 34:6]. Together they paint a powerful picture of God’s mercy: a bond of love rooted in the very womb of God with the power and tenderness of a mother’s love that is a totally unmerited gift, transcending what is fair and exceeding every human expectation. As Pope Francis puts it, “the mercy of God … reveals his love as that of a father or a mother, moved to the very depths out of love for their child. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that this is a ‘visceral’ love. It gushes forth from the depths naturally, full of tenderness and compassion, indulgence and mercy” [MV, 6]. This is our God — the God of the Old Testament as well as the New.

NEW TESTAMENT

The story of God’s mercy, of course, continues in the New Testament. As Pope Francis writes in the opening lines of Misericordiae Vultus:

Jesus Christ is the face of the Father’s mercy. These words might well sum up the mystery of the Christian faith. Mercy has become living and visible in Jesus of Nazareth, reaching its culmination in him.…[B]y his words, his actions, and his entire person [he] reveals the mercy of God [MV, 1].

At heart, Christianity is the Good News that in Jesus of Nazareth God has become one of us, has come as close to us as possible, and that this God with us, this Emmanuel, is a God of loving mercy. “The mission Jesus received from the Father was that of revealing the mystery of divine love in its fullness” [MV, 8]. The love shared among and defining the persons of the Trinity, the love shown in God’s acts of mercy to his people Israel, the love now made “visible and tangible in Jesus’ entire life” [MV, 8].

Illuminating this mystery are the teachings and actions of Jesus. A central theme of both his words and his deeds is the  Kingdom or the Reign of God. I often find “Reign of God” a more fruitful way to think about this because it suggests something more dynamic or active than a place. The Reign of God points to the activity of God reigning and to our response. In Jesus’ day there were not nations as we know them but kingdoms and empires. One way to think of a kingdom is that it exists where the king’s word has authority. Where a king or queen is obeyed, there is the kingdom. So the Kingdom of God is where God’s word has authority, where God is obeyed. Jesus’ call to the kingdom is for us to let God’s word reign in our lives here and now. When it does, we are living in the Kingdom, the Reign of God. This is not something that begins only after we die or at some future time.

Kingdom or the Reign of God. I often find “Reign of God” a more fruitful way to think about this because it suggests something more dynamic or active than a place. The Reign of God points to the activity of God reigning and to our response. In Jesus’ day there were not nations as we know them but kingdoms and empires. One way to think of a kingdom is that it exists where the king’s word has authority. Where a king or queen is obeyed, there is the kingdom. So the Kingdom of God is where God’s word has authority, where God is obeyed. Jesus’ call to the kingdom is for us to let God’s word reign in our lives here and now. When it does, we are living in the Kingdom, the Reign of God. This is not something that begins only after we die or at some future time.

The life and teaching of Jesus show us what that Reign of God is like, what we and our relations with others are like when God reigns in our lives. What he makes clear over and over is that the God who reigns is a God of mercy and that the Reign of this God is one where loving mercy shapes our lives and interactions. That is how the citizens of the Kingdom of God live. More locally, this is how the members of the Diocese of Saint Cloud are to live. Jesus also shows that the way of life in which God reigns, is different than our usual way of relating, the usual ways of the world.

Much of Jesus’ teaching about the Reign of God is done in parables, which, typically turn our expectations upside down —or, more accurately, right-side up. “In the parables of mercy,” Pope Francis observes:

Jesus reveals the nature of God as that of a Father who never gives up until he has forgiven the wrong and overcome rejection with compassion and mercy…. In them we find the core of the Gospel and of our faith, because mercy is presented as a force that overcomes everything, filling the heart with love and bringing consolation through pardon [MV, 9].

We will reflect briefly on three of these parables: the Prodigal Son, the Good Samaritan, and the Workers in the Vineyard. Each highlights an important feature of the Reign of God, the Reign of Mercy.

Prodigal Son — Merciful Father

The parable of the Prodigal Son or, as Pope Francis often refers to it, the Merciful Father [Lk 15:11-32], is well known. A father has two sons; the younger, showing great disrespect, asks for his share of the inheritance prior to his father’s death. He  deepens this disrespect by squandering his inheritance “on a life of dissipation.” The son can make no further claims on this father. He is owed nothing. Penniless and starving he heads home hoping to be one of his father’s workers. Despite all the son has done, the disrespect he has shown, and what he might justly deserve, the father remains his father, loves him and is merciful. When he sees his son at a distance, the father runs to his son. He does not wait for the son to beg for forgiveness or even explain what he has done or why he is there. He runs to him and embraces him. Beyond any reasonable expectation, the merciful father restores his son to his place in his home. His action is not based on a fair allocation of material goods — as the older brother understandably points out — but simply on the father’s love for his child which he expresses in bountiful, joyous mercy. This is how God is.

deepens this disrespect by squandering his inheritance “on a life of dissipation.” The son can make no further claims on this father. He is owed nothing. Penniless and starving he heads home hoping to be one of his father’s workers. Despite all the son has done, the disrespect he has shown, and what he might justly deserve, the father remains his father, loves him and is merciful. When he sees his son at a distance, the father runs to his son. He does not wait for the son to beg for forgiveness or even explain what he has done or why he is there. He runs to him and embraces him. Beyond any reasonable expectation, the merciful father restores his son to his place in his home. His action is not based on a fair allocation of material goods — as the older brother understandably points out — but simply on the father’s love for his child which he expresses in bountiful, joyous mercy. This is how God is.

Jesus makes a similar point in the parables of the Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin, which Luke presents just before the parable of the Merciful Father. Here the shepherd and the woman risk leaving the 99 to seek the one that is lost. Like them, God does not sit back and wait for the lost to turn and return. The merciful God goes out, lights a lamp, sweeps the house, does whatever it takes to find the lost and bring them home. This is how God reigns: acting out of love for us, to bring us home. As St. Paul says, “God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners Christ died for us” [Rom 5:8]. Significantly, the setting of these three parables is Jesus explaining to religious leaders why he “welcomes sinners and eats with them” [Lk 15:2] which is itself a manifestation of the reign of God in the actions of Christ.

Good Samaritan

In response to the question, “Who is my neighbor?” Jesus tells the parable of the Good Samaritan [Lk 10:29-37]. A man was beaten up by robbers and left for dead along the side of the road. A priest and a Levite (we might say a bishop and a theologian) passed by and did nothing, even crossing to the other side of the road. A Samaritan, considered an apostate and enemy by Jesus’ hearers (we might say a Muslim), was moved by compassion and helped him: treating his wounds, taking him to an inn, and paying for his care. What this parable adds to our picture of mercy and the Reign of God is the application to how we should act as citizens of this kingdom, when God’s word and God’s mercy reign in our lives.

Mercy is not a mere feeling or sentiment. It involves actions. God does not just have sympathetic feelings for us; he acts on our behalf throughout salvation history. The Samaritan did not just feel compassion toward the injured one; he acted to restore him to well-being, even at the cost of his time, resources, and comfort. This is what mercy looks like. Jesus ends the parable saying, “Go and do likewise.”

Jesus adds a further dimension to his command to go and do likewise in the parable of the unforgiving servant [Mt 18:21-35]. Peter asked Jesus how many times he must forgive one who has treated him badly. In other words, is there a limit to the mercy I am to show others? Jesus answers that he must forgive not just seven times but seventy-seven times, suggesting an unlimited number. He then tells the story of the unforgiving servant to show how mercy is to pervade the kingdom.

A servant who owed his master a great debt but could not pay was to be sold into slavery along with his whole family. He begs the master for mercy and time to repay the loan. “Moved with compassion, the master … let him go and forgave him the loan.” This servant then meets another who owed him a small debt and couldn’t pay. The second servant begs for mercy and time to repay the debt but the forgiven servant refuses and throws him in prison. When the master learns of this he calls in the one whose loan had been forgiven and says, “Should you not have had mercy on your fellow servant, as I had mercy on you? Then in anger his master handed him over to the torturers until he should pay back the whole debt.” Jesus concludes: “So will my heavenly Father do to you, unless you forgive your brother from your heart.”

The message could hardly be clearer: What we have received, we are to give to others. Pope Francis, commenting on this parable, says that it “contains a profound teaching for all of us. Jesus affirms that mercy is not only an action of the Father, it becomes a criterion for ascertaining who his true children are,” who is a citizen of the Kingdom of God in whom God’s word and God’s mercy reigns. “In short, we are called to show mercy because mercy has first been shown to us…. As the Father loves, so do his children. Just as he is merciful, so we are called to be merciful to each other” [MV, 9]. Hence the motto of this holy year: Merciful like the Father.

Workers in the Vineyard

A third characteristic of the life of mercy emerges in the parable of the workers in the vineyard [Mt 20:1-16]. Jesus compares the Reign of God to a landowner who went out at dawn to hire workers for his vineyard at the usual daily wage. He hired more workers throughout the day, some just an hour before sundown. In the evening he paid them all a full day’s wages. Those who were hired at dawn complained that this was not fair. They had worked much longer and through the heat of the day. The owner pointed out that they were not being cheated. They were paid a fair wage and what they agreed to. If he wanted to give the last the same as the first, he is free to do so. They should not be envious because he is generous.

The parable is troublingly clear in its disregard for what we think of as a proper exchange of reward for work. Here that is turned upside down — which is precisely the point. As God said in the Book of Hosea, the ways of God are not the ways of humans. The Reign of God is not the same as the reign of the rulers of this world. In the kingdom of the world, we relate to each other according to a basic economy of fairness in which the more we work the more we earn. Jesus is not suggesting that such fairness is evil. It is certainly better than cheating or taking advantage of others and not paying them justly or fairly. However, he is introducing us to the Reign of God which operates on an economy of gift. Here the unexpected, wild, even profligate love and mercy of God reigns. Our response to such generosity is all too often that of those who worked all day or the older brother of the prodigal son: grumbling and envy. We appeal to the fairness with which we are comfortable, assuming, of course, that if we were treated fairly, if we were given what we had earned, we would be better off than those others. But as children of God, as disciples in whom God’s love reigns, we are called to rejoice and give thanks for the generous mercy God has shown to all of us. And to go and do likewise.

The Life of Jesus

In addition to teaching about the Reign of God’s mercy in the parables and elsewhere, the life of Jesus also profoundly reveals the mercy of God, showing us what it looks like when this mercy reigns in one’s life. As Pope Francis puts it:

‘God is Love’ …. This love has now been made visible and tangible in Jesus’ entire life. His person is nothing but love, a love given gratuitously.… The signs he works, especially in favor of sinners, the poor, the marginalized, the sick, and the suffering, are all meant to teach mercy. Everything about him speaks of mercy. Nothing in him is devoid of compassion [MV, 8].

Jesus is open and welcoming to all who approach him. Much to the dismay of the religious leaders of his day, he eats with and even forgives sinners, prostitutes, tax collectors, the unclean and reviled of all sorts.

Jesus’ deeds of mercy and the kingdom he proclaimed were —are — very unsettling. They aroused suspicion and were regarded as scandalous because they did not conform to our expectations of what is proper and fair, of how life should be. As in the Garden of Eden, we really do think we know best. The envy we saw in the first workers in the vineyard and the prodigal’s brother turned to rejection and hostility, culminating in the execution of Jesus on the cross. Divine Love itself had become one of us, walking among us to show us the very face of mercy, to show us how to live a truly human, loving life. Once again, we humans rejected this love; we rejected the Reign of God, preferring our own, familiar way of doing things. “He came to what was his own, but his own people did not accept him” [Jn 1:11].

Yet here, at what is the lowest point in salvation history, our execution of the very Son of God, we see the most profound, unexpected demonstration of God’s mercy. Despite what we have done, despite what justice or fairness might demand, God does not destroy us or even abandon us. Even at the end, in the midst of his suffering and dying from our rejection of him, Jesus is merciful and forgiving: “Father, forgive them, they know not what they do” [Lk 23:34]. And God the ever merciful father is not done with his prodigal daughters and sons. In his infinite, unfathomable love, God does not allow rejection and death to have the last word. He raises Jesus to new life and pours out his own Spirit on his people. In mercy, God promises to be with us to the end of time.

As we have seen from creation onward, God’s love, not our rejection or sin, ultimately shapes our history and our relation with God. This is truly Good News. This is the mercy of God that is the source of our life and our hope. Our lives as Christians, as disciples of Jesus, begin in gratitude for the mercy we have received from God, the love that is the very foundation of our lives. We are called to live out of that mercy in our relations with others. What we have received, we are to give. “Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful” [Lk 6:36]. This is not only the motto of the Holy Year; it is the beating heart of the Christian life.

III

MERCY, UNCONDITIONAL LOVE AND JUSTICE

What emerges from the rich tapestry of Scripture is a picture of God as a father who loves us, his children, unconditionally. This is the mystery and the reality of God’s mercy. Such unconditional love is truly one of the great gifts and great mysteries of life. It can be hard to understand, especially so formed as we are by a world of exchange. It can be hard to give and at times even hard to accept. We sometimes want to think we have earned the love we receive. But the gift of unconditional love is a mystery that parents and children know first-hand — at least we hope so. At their best, parents love their children unconditionally. No matter what they do, one’s children are loved. Certainly, we want children to know — and it is a parent’s responsibility to teach them — that actions have consequences, including punishment. But the loss of the parent’s love is not one of the consequences. That is the point of love being unconditional.

So too with God as our Father. God is certainly no less loving a parent than humans are. As humans we are responsible for our actions. There are consequences. Scripture is quite clear about that. But it is also clear that God never stops loving us. Even when we break our promises, do not keep our end of the bargain, squander our inheritance on false gods of all sorts, God remains faithful to his promises and his love for us. Scripture assures us, most powerfully in the Resurrection, that God will never abandon us. There is nothing we can do that is so bad that God will abandon us — not even the killing of his son. This at heart is the mystery of God’s mercy.

The idea of unconditional love and the focus on God’s mercy raise the age-old question of the relation of justice and mercy. If all is forgiven and God loves us no matter what we do, what is the place of justice? Surely there is a difference between good and bad, right and wrong. Should not those who do wrong pay a price of some kind? Why not just do whatever we want, confident that, like the prodigal, we will be welcomed home? Is not justice important to maintaining order in society and even in God’s universe?

The Holy Father addresses this directly in his letter on the Year of Mercy.

[J]ustice and mercy … are not contradictory realities but two dimensions of a single reality that unfolds progressively until it culminates in the fullness of love. Justice is a fundamental concept for civil society, which is meant to be governed by the rule of law. Justice is also understood as that which is rightly due to each individual” [MV, 20].

Justice is not the opposite of mercy. Rather, justice is part of the larger reality of mercy. It contributes to the work of mercy as a means to an end with the ultimate goal being a relationship of love. When this order is turned around, when justice becomes the end rather than a means, when justice rather than mercy is our primary message, we end up with the kind of legalism of which Jesus was so critical, which distorts “the original meaning of justice and [obscures] its profound value” [MV, 20].

Justice is thus not just a set of rules, but rules about mercy. It puts flesh on what can be the abstract principles of mercy. Justice shows us what it looks like when we exercise mercy; how we are to treat others and how we can expect to be treated. Specifically, justice is about what is rightly due to each person as a function of his or her dignity as a human being, not from the generosity of those in power. Scripture speaks most passionately in both the Old and New Testaments about the demands  of justice for those who have no one to look out for them: the widows and orphans, the poor, the weak, the outcast, the aliens in our midst. What the messiahship of Jesus, the lowly and crucified one, makes clear is that the chosen people, the blessed community, those who know the mercy of God, are called not to rule but to serve, especially the poor and those who have no one else to care for them. We are called to work towards a society that better reflects these expectations of justice for all God’s children. This is how we participate in the work, the love and mercy of God. As Pope Francis puts it, “Charity that leaves the poor person as he or she is, is not sufficient. True mercy, the mercy God gives to us and teaches us, demands justice; it demands that the poor find the way to be poor no longer.” (2)

of justice for those who have no one to look out for them: the widows and orphans, the poor, the weak, the outcast, the aliens in our midst. What the messiahship of Jesus, the lowly and crucified one, makes clear is that the chosen people, the blessed community, those who know the mercy of God, are called not to rule but to serve, especially the poor and those who have no one else to care for them. We are called to work towards a society that better reflects these expectations of justice for all God’s children. This is how we participate in the work, the love and mercy of God. As Pope Francis puts it, “Charity that leaves the poor person as he or she is, is not sufficient. True mercy, the mercy God gives to us and teaches us, demands justice; it demands that the poor find the way to be poor no longer.” (2)

Justice and mercy also work together on the more individual level. In the words of the Holy Father:

Mercy is not opposed to justice but rather expresses God’s way of reaching out to the sinner offering him a new chance to look at himself, convert, and believe…. If God limited himself to only justice he would cease to be God.… This is why God goes beyond justice with mercy and forgiveness. Yet this does not mean that justice should be devalued or rendered superfluous. On the contrary: anyone who makes a mistake must pay the price. However, this is just the beginning of conversion not its end, because one begins to feel the tenderness and mercy of God. God does not deny justice. He rather envelops it and surpasses it with an even greater event in which we experience love as the foundation of justice” [MV, 21].

Mercy, unconditional love, does not mean nothing matters. When we do something wrong we must pay the price. This is just.  The fact that one is forgiven does not mean the consequences end. That is to misunderstand the nature of forgiveness and of transformation. Imagine the following situation: A young person has a pattern of reckless behavior, of showing no respect for the property of others. One day this person drives through a neighbor’s prized flower bed, destroying it. As a consequence, as punishment, the driver needs to earn the money to replace the plants, work the soil, replant and nurture the plants through the summer. The driver may be contrite and the neighbor may even forgive him or her. But that does not mean the work on restoring the flower bed ends. Justice means that work, the consequences of the recklessness, continues even though one is forgiven. Indeed, true contrition recognizes the need for restitution. The hope is that the “punishment” will teach him or her to be more respectful and careful. Mercy and justice work together for the good of all with justice ultimately serving the work of mercy. And whatever the consequences, however severe the situation may be, the child does not lose the love of parents or of God.

The fact that one is forgiven does not mean the consequences end. That is to misunderstand the nature of forgiveness and of transformation. Imagine the following situation: A young person has a pattern of reckless behavior, of showing no respect for the property of others. One day this person drives through a neighbor’s prized flower bed, destroying it. As a consequence, as punishment, the driver needs to earn the money to replace the plants, work the soil, replant and nurture the plants through the summer. The driver may be contrite and the neighbor may even forgive him or her. But that does not mean the work on restoring the flower bed ends. Justice means that work, the consequences of the recklessness, continues even though one is forgiven. Indeed, true contrition recognizes the need for restitution. The hope is that the “punishment” will teach him or her to be more respectful and careful. Mercy and justice work together for the good of all with justice ultimately serving the work of mercy. And whatever the consequences, however severe the situation may be, the child does not lose the love of parents or of God.

Again, Jesus, mercy incarnate, is our model. He speaks often and forcefully of the destructive power of sin and evil, calling us to follow the commandments of God, to live according to the beatitudes and, to “sin no more” [Jn 8:11]. In short, to let God reign in our lives. However, while he rejects the sin, he does not reject the sinner. Hence the ancient adage: hate the sin but love the sinner. Jesus eats with sinners not because he doesn’t know they are sinners or thinks that what they have done is OK but because he loves them. So must it be with us, his disciples.

That love includes speaking the truth about sin and a call to conversion. Sinful behavior is harmful to others and to the sinner. It would hardly be loving to stand by and do nothing. Mercy without truth is not authentic. However, it is no less true and must always be said at the same time that truth without mercy is arrogant and destructive. The truth about sin is not only or even primarily a truth about others. It is first a truth about oneself. As Pope Francis observes, “One who believes may not be presumptuous; on the contrary, truth leads to humility, because believers know that, rather than ourselves possessing truth, it is truth that embraces and possesses us” [CM, 8]. Speaking the truth about sin and appeals to justice all too easily become self-righteous, as if we are the norm of what is right and good or at least have met the standards of justice while others fall short. It is those who succumb to such self-righteousness who are the objects of Jesus’ greatest scorn in the Gospels. So the Holy Father reminds us that “The Lord asks us above all not to judge and not to condemn. If anyone wishes to avoid God’s judgement he should not make himself the judge of his brother or sister” [MV, 14, See Lk 6:37-38]. Recognizing the place of justice does not mean we are the judge.

Thus we return to the truth that justice and mercy work together as “two dimensions of a single reality”— a reality that “culminates in the fullness of love.” Justice must be understood as operating in the service of mercy. It is “only the first, albeit necessary and indispensable step. But the Church needs to go beyond and strive for a higher and more important goal” [MV, 10], namely, mercy. Love and mercy envelope justice and are the foundation of justice. Thus the Holy Father notes on opening the Holy Door in Saint Peter’s to inaugurate the Year of Mercy, “How much wrong we do to God and his grace when we speak of sins being punished by his judgment before we speak of their being forgiven by his mercy! But that is the truth. We have to put mercy before judgment, and in any event God’s judgment will always be in the light of his mercy.” (3)

Thank God! All of us, saints and sinners, rely on God’s mercy, not on justice or our own worthiness as our hope for salvation. “Mercy is the very foundation of the Church’s life…. [W]ithout a witness to mercy, life becomes fruitless and sterile…. The time has come for the Church to take up the joyful call to mercy once more…. Mercy is the force that reawakens us to new life and instills in us the courage to look to the future with hope” [MV, 10] It is this life-giving, hope-filled work of mercy that justice — and the Church — must serve.

IV

A CHURCH OF MERCY

God has entrusted the continuing work of mercy in a special way to his Church, both individually in the work of all who are disciples of Christ, and collectively in the work of the Church as a community and institution. The Holy Father makes clear that this work of mercy goes to the very heart of what it means to be church and of our identity, our mission, as Christians.

Mercy is the very foundation of the Church’s life. All of her pastoral activity should be caught up in the tenderness she makes present to believers; nothing in her preaching and in her witness to the world can be lacking in mercy. The Church’s very credibility is seen in how she shows merciful and compassionate love [MV, 10].

The Church is commissioned to announce the mercy of God, the beating heart of the Gospel…. The Spouse of Christ must pattern her behavior after the Son of God…. It is absolutely essential for the Church and for the credibility of her message that she herself live and testify to mercy. Her language and her gestures must transmit mercy so as to touch the hearts of all people and inspire them once more to find the road that leads to the Father [MV, 12].

“The Church feels the urgent need to proclaim God’s mercy. Her life is authentic and credible only when she becomes a convincing herald of mercy…. The Church is called above all to be a credible witness to mercy professing it and living it as the core of the revelation of Jesus Christ” [MV, 25].

There are three things I would like to highlight in these compelling passages. First, we as church, both individually and collectively, are called to “announce,” “proclaim” and bear “witness” to the mercy of God. However, this witnessing involves more than words. Our witness as church to the mercy of God requires us to make this mercy present in our lives and in the world in which we live. We are not just witnesses to God’s loving mercy; we are agents of that mercy in the world. Our call, our vocation and privilege as followers of Christ, is to participate in God’s merciful love for the world — for all God’s children. Our mercy is the concrete form of God’s mercy in the world.

A second dimension of this witness and agency emerges when we think of the Church as a sacrament of mercy. Rooted in the Incarnation, sacrament refers to a material reality that makes present — really present — the immaterial reality of God’s grace, the Spirit of God with us. The Second Vatican Council added the image of the Church as the sacrament of Christ’s continuing presence in the world to those of Mystical Body or People of God. Having identified Christ as the incarnation of God’s mercy, it is appropriate to see the Church as the sacrament of God’s mercy. We are to be a living and effective sign of God’s love in the world, a sign that does not just point to the love of God but makes it really present among us.

One of the advantages of thinking of the Church as a sacrament of mercy is that sacraments involve very concrete, tangible elements: water, bread, wine, oil. So if the Church is a sacrament of mercy, what are the concrete, material forms or elements in which mercy is present in our parishes, in the diocese as a whole, and in our lives outside the parish? How are we making the mercy of God really present in the world? How do we experience this mercy? How do we share it? Moreover, the ministers of this sacrament are not a particular group ordained for the work of mercy but all of the baptized. All of us as disciples are called to make the mercy of God present in our lives and the world in which we live. This is what it means to be church.

Third, nothing less than our credibility as church is at stake in this work of mercy — not to mention our faithfulness to the God who entrusts us with the work of being the sacrament of his mercy in the world. If we and our proclamation of the Gospel are to have credibility in the world, we must not only talk about mercy we must practice it. This practice of mercy must be evident in our actions as individual members of the Church and in the activities of the institutional Church at all levels: parish, diocese, global. Pope Francis describes what this means in Evangelii Gaudium: The Joy of the Gospel, “The Church must be a place of mercy freely given, where everyone can feel welcomed, loved, forgiven and encouraged to live the good life of the Gospel” [114]. Likewise, in speaking of the holiness of the Church, he notes:

Throughout history, some have been tempted to say that the Church is the Church of only the pure and the perfectly consistent, and it expels all the rest. This is not true! This is heresy! The Church, which is holy, does not reject sinners; she does not reject us all; she does not reject us because she calls everyone, welcomes them, is open to those furthest from her…. The Lord wants us to belong to a Church that knows how to open her arms and welcome everyone, that is not a house for the few, but a house for everyone, where all can be renewed, transformed, sanctified by his love — the strongest and the weakest, sinners, the indifferent, those who feel discouraged or lost” [CM, 31].

In imitation of Christ, we must put forgiveness ahead of judgment, openness ahead of exclusion, bridges before walls. This must be expressed in our gestures, attitudes and actions even more than in our words. This practice of mercy is necessary for the new evangelization to be effective in reaching those who have abandoned the Church, often because the Church simply has no credibility for them. It is this practice of mercy that Pope Francis seeks to reinvigorate through this Holy Year of Mercy.

V

A YEAR OF MERCY

A holy or jubilee year is a special time of spiritual renewal traditionally characterized by three things: opening the Holy Door at Saint Peter’s in Rome, pilgrimage to and through the Holy Door, and a special indulgence. All are true of this Jubilee Year of Mercy with the addition of a focus on renewing our experience and practice of mercy.

Holy Door

The opening of the Holy Door at Saint Peter’s and the other papal basilicas in Rome has always been the central symbol of a holy year. It is the focus of the spiritual renewal sought in a jubilee  year, with the doorway symbolizing a movement from one place in one’s life to another; a conversion from sin to grace; from isolation, doubt, or shame to community, faithfulness, and reconciliation; a passageway to a closer relation to God and a richer life of discipleship. An open door is a particularly fitting symbol for this Year of Mercy, expressing the openness of the church, the hospitality of God’s mercy and of the Church as the sacrament of that mercy. As Pope Francis put it when he announced the Holy Year, “No one can be excluded from the mercy of God…. And the Church is the house where everyone is welcomed and no one is rejected. Her doors remain wide open, so that those who are touched by grace may find the assurance of forgiveness.” (4) Thus the Holy Door is “a Door of Mercy through which anyone who enters will experience the love of God who consoles, pardons, and instills hope” [MV,3].

year, with the doorway symbolizing a movement from one place in one’s life to another; a conversion from sin to grace; from isolation, doubt, or shame to community, faithfulness, and reconciliation; a passageway to a closer relation to God and a richer life of discipleship. An open door is a particularly fitting symbol for this Year of Mercy, expressing the openness of the church, the hospitality of God’s mercy and of the Church as the sacrament of that mercy. As Pope Francis put it when he announced the Holy Year, “No one can be excluded from the mercy of God…. And the Church is the house where everyone is welcomed and no one is rejected. Her doors remain wide open, so that those who are touched by grace may find the assurance of forgiveness.” (4) Thus the Holy Door is “a Door of Mercy through which anyone who enters will experience the love of God who consoles, pardons, and instills hope” [MV,3].

Open doors not only welcome people in, they also allow those who are inside to go out. So too with the Door of Mercy. As Christians we are to imitate the God of mercy whose love leads him to go out of himself to be with us in Jesus who in turn goes out of himself for all of us. We must not “be satisfied with staying in the pen of the ninety-nine sheep” but must go out with the good shepherd and the housewife to seek the lost [CM, 73]. We are not to just wait for people to come in but, like the merciful father, are to go out to meet them where they are, bringing the good news of God’s mercy to them in our words and deeds.

This openness and going out, notes Pope Francis, is the spirit of the Second Vatican Council and the work of the Holy Spirit that he wants to keep alive. As noted earlier, by opening the Holy Door on the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Council, the Holy Father explicitly connects the Year of Mercy to the Council. “Before all else,” he explains:

The Council was an encounter. A genuine encounter between the Church and the men and women of our time. An encounter marked by the power of the Spirit, who impelled the Church to emerge from the shoals which for years had kept her self-enclosed so as to set out once again with enthusiasm, on her missionary journey. It was the resumption of a journey of encountering people where they live: in their cities and homes, in their workplaces. (5)

The walls which for too long had made the Church a kind of fortress were torn down and the time had come to proclaim the Gospel in a new way. It was a new phase of the same evangelization that had existed from the beginning [MV, 4].

The Council moves us from an understanding of the Church as a fortress for the saved or the holy with its doors closed against the world to a field hospital with its doors open to serve the wounded, the damaged, the needy. The energy that may have gone into building walls is to be directed to building bridges to enable disciples to go out as agents of God’s mercy and to enable all to find their way in to experience the community of God’s mercy.

During this Holy Year we seek to cultivate this open-door spirit and practice of mercy in the Diocese of Saint Cloud. Following the Holy Father’s invitation, I have designated the center door of St. Mary’s Cathedral as a Holy Door for the diocese with a special seal to mark the Year of Mercy. On December 13 I opened the door to receive all who wish to pass through as a sign of entering into God’s mercy. It is a sign both of our openness as the Church of Christ and of our actively going out to extend God’s mercy to all in need in the diocese, which is to all. I call on each member of the diocese, each parish, diocesan office, agency and school to identify at least one thing you can do this year to extend and make present in the diocese the openness, the welcome and hospitality of God’s mercy, symbolized by our open Holy Door. Lest we think this is only about specifically religious or church-related activities, I ask each of you to consider also how you can express the openness of God’s mercy in your personal, family, professional, and civic lives. We are to be agents of God’s mercy, to be church, in all we do, not just when we are doing what we might think of as “churchly” things.

What the Holy Father said in opening the Holy Door at Saint Peter’s Basilica applies equally to the Holy Door of St. Mary’s Cathedral: “To pass through the Holy Door means to rediscover the infinite mercy of the Father who welcomes everyone and goes out personally to encounter each of them” — each of us. “The Jubilee challenges us to this openness, and demands that we not neglect the spirit which emerged from Vatican II, the spirit of the Samaritan…. May our passing through the Holy Door … commit us to making our own the mercy of the Good Samaritan.”

Pilgrimage

The Holy Door is closely tied to the second feature of a Jubilee Year: Pilgrimage. Passing through the Holy Door, in Rome, Saint Cloud, or elsewhere, is the tangible goal of the pilgrimage in the Holy Year. A physical pilgrimage to a holy site represents the journey that is our life in which both the destination and the journey can be transformative. Consciously setting out on a pilgrimage encourages us to reflect on the goal and the path of our lives. During this Year of Mercy, we are called to think in a particular way about how the mercy we have received and the mercy we practice towards others are and are not part of our life journey. Pilgrimage is thus “a sign that mercy is also a goal to reach and requires dedication and sacrifice.” It is to be “an impetus toward conversion….” such that “by crossing the threshold of the Holy Door, we will find the strength to embrace God’s mercy and dedicate ourselves to being merciful with others as the Father has been with us” [MV, 14]. This Year of Mercy is a call to redirect our lives to experience God’s mercy and share it with others more fully. As we do so, we are changed and transformed, we pass through the doorway into new life.

While pilgrimage to Rome is certainly encouraged, the Holy Father is aware that the cost and other difficulties of the travel make this impractical for many in the church. He also wants to root the experience and celebration of Divine Mercy in the local, diocesan, church. Thus he is expanding the practice to include pilgrimages in local dioceses. In that spirit, I invite all the faithful of the Diocese of Saint Cloud to visit the Cathedral during this Year of Mercy and pass through the Holy Door as an outward sign of our inward pilgrimage to conversion of heart and renewal of a lifestyle of mercy. I have also designated other pilgrimage sites in the diocese:

• The Shrine of Saint Peregrine, Martyr, Saint John’s Abbey, Collegeville

• The National Shrine of Saint Odilia, Crosier Priory, Onamia

• Assumption (Grasshopper) Chapel, Cold Spring

• Divine Mercy Shrine, Saint Paul Church, Sauk Centre

• The Shrine of Saint Cloud, Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Saint Cloud

In addition, I encourage all to pray at least once during this Holy Year at Mass or another liturgical event with the religious communities that have been and continue to be so important to the life and witness of our diocese:

• The Sisters of Saint Benedict’s Monastery, Saint Joseph

• The monks of Saint John’s Abbey, Collegeville

• The Franciscan Sisters, Little Falls

• The Crosier Fathers and Brothers, Onamia

• The Poor Clare Sisters, Sauk Rapids

Often the most transformative journeys are those taken in the company of others. Thus, where possible, I encourage you to put together a group, be it family, parish, class, organization such as Knights of Columbus, Catholic Daughters, DCCW, or others, to make a pilgrimage together to one or more of these holy places and communities and to use this as an occasion to pray and talk together about the place of mercy in our lives: the mercy we have received and the mercy we give. My hope is that these pilgrimages might take us not only to holy places but to holy lives, lives filled with mercy, reconciliation and love, lives lived in the Reign of God.

Sacrament of Reconciliation

The Holy Father links this practice of pilgrimage “first and foremost to the sacrament of reconciliation and to the celebration of the Holy Eucharist with a reflection on mercy.” (6) All sacraments are sacraments of mercy, of God’s loving presence with us, but the sacrament of  reconciliation is a particularly focused and particularly powerful sacrament of God’s mercy. It makes tangible God’s eagerness to forgive. Here we experience in a very concrete, interpersonal way the mercy and forgiveness of God acting through the Church and the person of the confessor.

reconciliation is a particularly focused and particularly powerful sacrament of God’s mercy. It makes tangible God’s eagerness to forgive. Here we experience in a very concrete, interpersonal way the mercy and forgiveness of God acting through the Church and the person of the confessor.

In the sacrament of reconciliation, Christ invites us on a journey to new life. It begins with a serious reflection on the quality and character of our life of discipleship, on those times when we may have failed to live up to the gift of mercy we have received, when we have not loved God or our neighbor as we are called to do, when we have not let God reign in our lives. Confessing this, however, is only the beginning of the sacrament. The end, the goal that God seeks is reconciliation. As with the prodigal son, God does not dwell on the pain of our going away or our sorrow for all we have done to distance ourselves from God. The sacrament of reconciliation is ultimately about the joy of homecoming — of passing through the holy door to rejoin God and our divine family.

As with all the sacraments, the physical character of the sacrament of reconciliation is part of its gift to us. Speaking our sins out loud to another person focuses the mind and heart on our specific actions and attitudes that do not live up to commitment to follow Christ. This is not easy. It can make confession and repentance painfully real. At the same time, hearing the words “Your sins are forgiven” spoken in the name of Jesus Christ and addressed directly to me is an even more powerful experience of the mercy of God. This reconciliation truly is something to celebrate.

As with all the sacraments, the physical character of the sacrament of reconciliation is part of its gift to us. Speaking our sins out loud to another person focuses the mind and heart on our specific actions and attitudes that do not live up to commitment to follow Christ. This is not easy. It can make confession and repentance painfully real. At the same time, hearing the words “Your sins are forgiven” spoken in the name of Jesus Christ and addressed directly to me is an even more powerful experience of the mercy of God. This reconciliation truly is something to celebrate.

Thus the sacrament of reconciliation stands at the heart of the Jubilee of Mercy. Whether it be part of a pilgrimage or whether the journey to reconciliation is itself a pilgrimage in one’s life, I encourage all in the diocese to celebrate the sacrament of reconciliation during the season of Lent and at other times throughout this Year of Mercy. And remember, “God forgives all and God forgives always.” (7) No action and no person is beyond the mercy of God and his eagerness to be reconciled with each of us.

To the priests, the confessors of the diocese, I ask you to receive the sacrament yourselves and I join the Holy Father in “insisting that [you] be authentic signs of the Father’s mercy…. Let us never forget that to be confessors means to participate in the very mission of Jesus to be a concrete sign of the constancy of divine love that pardons and saves…. Every confessor must accept the faithful as the father in the parable of the prodigal son: a father who runs out to meet his son despite the fact that he has squandered his inheritance” [MV, 17]. We represent Christ by welcoming people home with mercy and forgiveness, not judgment.

As a special focus of our diocesan Jubilee of Mercy, I am asking our priests and parishes to offer a Festival of Forgiveness in which the sacrament of reconciliation will be celebrated for twelve continuous hours from 10:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. in one or two sites in every deanery on March 4, 2016. During the early weeks of Lent, please invite as extensively and effectively as possible all Catholic people to experience again the love and mercy of God through the sacrament of reconciliation. Make a special effort to invite those who may not have received the sacrament for some time or who may feel alienated from the Church for any reason.

You may have heard that Pope Francis is appointing Missionaries of Mercy to be sent out into the world to facilitate activities around the Year of Mercy. If the diocese can benefit from the presence of a Missionary of Mercy and someone is available I will provide additional information about such a visit.

In this Holy Year, particularly in this season of Lent, let us follow the lead of the Holy Father in the diocese and “place the Sacrament of Reconciliation at the center … in such a way that it will enable people to touch the grandeur of God’s mercy with their own hands” [MV, 17].

Indulgence

Closely connected to the Holy Door, Pilgrimage, and Reconciliation is the third traditional feature of a Holy Year: the granting of a special Jubilee Indulgence. Noting that it is particularly fitting for the Year of Mercy because it shows how “God’s forgiveness knows no bounds” [MV, 22], Pope Francis has granted a General (plenary) Indulgence for all those who faithfully make a pilgrimage through a designated Holy Door. He urges all to link this pilgrimage with a celebration of the sacrament of reconciliation and the Eucharist. The Holy Father recognizes that some are not able to go on pilgrimage because they are homebound through illness or age or are incarcerated. For them, “Living with faith and joyful hope this moment of trial, receiving Communion or attending Holy Mass and community prayer even through the various means of communication will be … the means of obtaining the Jubilee Indulgence.” He specifically invites the incarcerated to make their cell door a holy door as they rely on the mercy of God. (8)

As we approach the 500th anniversary of the Reformation it is important that we properly understand the Church’s teaching on indulgences, which was a catalyst for the division in the Church and is especially important in the context of a reflection on God’s mercy. First of all, we need to be clear on what this teaching is not: It is not about earning forgiveness. This would be contrary to the whole revelation and Church teaching on God’s mercy summarized in this letter. God forgives us while we are yet sinners. This forgiveness, grace, mercy is unmerited, an act of God’s unconditional love for us. It is not earned through our works of righteousness, our keeping the law, exemplary virtue, Mass attendance, or anything else we do. God simply loves us and forgives as the merciful father he is.

The idea of God’s indulgence, which is what this practice is about, must be understood within that basic revelation of God’s unconditional love. Indeed, properly understood, indulgence is a further manifestation of God’s merciful love. The key is the distinction between forgiveness and the consequences of the actions for which we are forgiven. Even though we have been truly forgiven and have accepted that forgiveness with a genuine conversion of heart, the consequences of sin — as we all know from personal experience — remain operative in our lives. We continue to struggle with negative behaviors and attitudes that have become habitual. As noted in our discussion of justice and mercy, there are also penalties or reparations to be made. In general, even when truly forgiven there is a transformation that needs to happen to live more fully in imitation of Christ. Sacramentally, we can say that while our sins are fully absolved in the sacrament of reconciliation, we still live with the pain and challenges that sin leaves in its wake.

Indulgence is about these consequences, not about the forgiveness already given. The idea is that God, in an act of indulgent mercy, removes the stain of sin and fosters healing of those parts of ourselves that still give us pain or that continue to hurt others. It is a recognition of the need to expand the reality of forgiveness into all aspects of the human experience so that we might “grow in love rather than … fall back into sin.” In the words of the Holy Father:

to live the indulgence of the Holy Year means to approach the Father’s mercy with the certainty that his forgiveness extends to the entire life of the believer. To gain an indulgence is to experience the holiness of the Church, who bestows upon all the fruits of Christ’s redemption, so that God’s love and forgiveness may extend everywhere. Let us live this Jubilee intensely, begging the Father to forgive our sins and to bathe us in his merciful ‘indulgence’ [MV, 22].

Indulgences are tied to particular activities because there are things we can do to show our seriousness about reorienting our lives. Indulgence is granted to recognize and encourage that activity. The gift of the indulgence can also extend to people connected to us, even if they have died. I therefore invite all the faithful to experience the merciful indulgence of God in this Jubilee Year by making a pilgrimage to the Cathedral of Saint Mary or other designates sites. I also invite you to consider ways in which you may practice the Works of Mercy as a way to participate in and manifest the mercy of God.

Works of Mercy

In addition to the practice of pilgrimage to the holy door with a jubilee indulgence, Pope Francis has added an additional feature to this holy year: an emphasis on the corporal and spiritual works of mercy as part of the practice of the holy year. In the words of the Holy Father:

It is my burning desire that, during this Jubilee, the Christian people may reflect on the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. It will be a way to reawaken our conscience, too often grown dull in the face of poverty. And let us enter more deeply into the heart of the Gospel where the poor have a special experience of God’s mercy. Jesus introduces us to these works of mercy in his preaching so that can know whether or not we are living as his disciples” [MV, 15].

To encourage the practice of the works of mercy and integrate that practice more fully into the Holy Year, Pope Francis has extended the Jubilee Indulgence to whomever undertakes one of these Works of Mercy and for every time they do so.

The church’s ancient tradition identifies seven corporal or bodily works of mercy and seven spiritual works of mercy:

Corporal Works of Mercy

Feed the hungry

Give drink to the thirsty

Clothe the naked

Welcome the stranger/Shelter the homeless

Visit/heal the sick

Visit the imprisoned

Bury the dead

Spiritual Works of Mercy

Counsel the doubtful

Instruct the ignorant

Admonish sinners

Comfort the afflicted

Forgive offenses

Bear wrongs patiently

Pray for the living and the dead

Together these constitute a beautiful and powerful image of the life of mercy and the Christian life generally. These two sets of actions focus our attention on particular, concrete things we can do to address the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of our neighbor. And who is our neighbor? This of course is precisely the question Jesus answers with the parable of the Good Samaritan in which he shows that our neighbor is whoever we meet who needs our care. Mercy and our acts of mercy are not limited to people in the Church or those who think and believe like we do. The command is to be merciful to any and all. We also learned from the Good Samaritan that mercy is not merely a feeling or sentiment. It must be made real in our concrete, particular actions to meet the actual needs of actual people. The works of mercy do exactly that, meeting the actual needs of our neighbors.

This Year of Mercy is an opportunity for all of us in the diocese to think concretely about our neighbors, their needs, and the works of mercy we can do to help them meet those needs. A letter like this cannot identify all those needs or the ways we might meet them. That is something each person, parish, and organization of the diocese needs to do in their situation, with their particular resources. I call on all people of the diocese to prayerfully consider the Works of Mercy and discern specific activities you can do to show mercy to your neighbors, to make ourselves and our church more an instrument of God’s mercy in our diocese. I encourage you to do this individually, in families, and in parish study groups that I hope will be formed around the theme of divine mercy.

As you engage in this discernment, consider not only your personal, individual relationships but also your collective social, civic, economic, political, and professional life as well. Some works of mercy are personal, one-to-one, actions and some are best done with others be it in ad hoc arrangements or through social agencies of one sort or another. There are longstanding organizations related to the diocese that are specifically dedicated to carrying out aspects of our collective work of mercy such as Catholic Charities, Saint Cloud Hospital, and the various Catholic schools in the diocese. Please consider whether your call to the work of mercy or that of your parish might include participation in the work of these or other offices and organizations of the diocese. In a particular way I encourage pastors and others who minister to the concrete needs of their communities to make God’s mercy a theme of their preaching, teaching, and pastoral care.

As we consider the concrete opportunities to show mercy, I ask you to consider two areas of need that I see as particularly pressing in our diocese. One that is especially prominent and likely to become more so in the year ahead has to do with immigrants and refugees, what Scripture refers to as “the aliens in our midst.” The U.S. bishops have been clear and consistent in calling the Church  (and the nation) to treat these people as the neighbors that they are: extending hospitality, care, and mercy to them as Jesus commands us to do. (9) In our diocese we encounter these immigrants primarily in two very different communities: Latino/as and Somalis. Our Latino/a neighbors tend to share our Christian, Catholic faith yet are still often made to feel unwelcome. Our Somali neighbors are primarily Muslim which magnifies our separation and all too often leads to suspicion and hostility. Challenging though these differences can be, we are no less called to show them mercy — not just a general feeling but concrete works of mercy evident in our behavior and policies. Here we encounter the challenge of the Good Samaritan that mercy is not only for those who think and believe like I do.

(and the nation) to treat these people as the neighbors that they are: extending hospitality, care, and mercy to them as Jesus commands us to do. (9) In our diocese we encounter these immigrants primarily in two very different communities: Latino/as and Somalis. Our Latino/a neighbors tend to share our Christian, Catholic faith yet are still often made to feel unwelcome. Our Somali neighbors are primarily Muslim which magnifies our separation and all too often leads to suspicion and hostility. Challenging though these differences can be, we are no less called to show them mercy — not just a general feeling but concrete works of mercy evident in our behavior and policies. Here we encounter the challenge of the Good Samaritan that mercy is not only for those who think and believe like I do.

The Holy Father is quite explicit in calling us to extend mercy to those “beyond the confines of the Church.” He calls us to show them mercy as children of God, with all the dignity that goes with that birthright, and even to learn from their traditions of mercy. “I trust that this Jubilee Year celebrating the mercy of God will foster an encounter with [Judaism and Islam] and with other noble religious traditions; may it open us to even more fervent dialogue so that we might know and understand one another better; may it eliminate every form of closed-mindedness and disrespect, and drive out every form of violence and discrimination” [MV, 23]. We need to find ways to practice such mercy in the Diocese of Saint Cloud, particularly to our Muslim neighbors. I encourage each of you, individually and in whatever groups you may be part of, to think of what you can do to contribute to that practice of mercy.

A second area of concern moves beyond the traditional works of mercy to consider how we might show mercy to the planet. In his encyclical, Laudato Si’: On Care for our Common Home, Pope Francis reminds us that human life, according to Scripture, “is grounded in three fundamental and closely intertwined relationships: with God, with our neighbor, and with the earth itself” [66]. We have considered the place of mercy in our relation with God and our neighbor. It is important that we at least note the call to mercy in our relation to the world.

A central theme of Laudato Si’ is that the world has an intrinsic dignity as God’s creation that must be respected. (10) As we have seen, God’s mercy is at work in the very act of creation. We are called to participate in and make present God’s mercy to creation as well as in God’s mercy to our fellow human beings. This is part of what it means to be a sacrament of mercy. Historically, we have tended to think of our relation to the world less in terms of respecting its dignity and more in terms of the dominion that we were granted in Genesis 1:28. Not only that but we think of and, more importantly, exercise this dominion more in the manner of the kingdoms of the world than the Reign of God. We all too often have acted as if our dominion means we can do whatever we want to the planet; that it exists for our pleasure — and our immediate, physical pleasure at that. Pope Francis observes, citing Saint John Paul II, that “This [understanding of] dominion over the earth…seems to have no room for mercy.” (11)

The Holy Father calls us to rethink the character of our dominion and change the way we exercise it. The dominion we are given is nothing less than a generous participation in God’s dominion. It is part of our being made in the image of God and entrusted with the gift of the earth as our home. The model for our dominion is thus the dominion of God which is a dominion — a reign — of mercy. It is a reign that consistently calls us to use the resources entrusted to us for the good of all, not just for ourselves. In the words of Pope Francis, “our ‘dominion’ over the universe should be understood more properly in the sense of responsible stewardship” [LS, 116]. God has entrusted the earth to our care and our stewardship of it is not only for ourselves but for all generations to come. Such stewardship is an act of mercy not only to the earth itself but to those generations yet to be born who will live in this home after we have gone. It is imperative that we do all we can to leave it to them in as good shape as it was when it was left to us.

As you consider particular works of mercy you can do during this Jubilee Year, I urge you to think about what you, your parish and the diocese can do to show mercy to the earth, our shared home, and to all those who will live in it after we are gone. Beyond the Church per se, what can you do to manifest such mercy towards creation in your business, farm, personal consumption, and public policy?

As we in the diocese make our pilgrimage through the Jubilee Year of Mercy, let us take to heart the Holy Father’s reminder that “The Church is called above all to be a credible witness to mercy, professing it and living it as the core of the revelation of Jesus Christ” [MV,25]. Each of us, as baptized members of the Body of Christ are commissioned to be agents of God’s mercy, to be ministers of the sacrament of mercy that is the Church in all areas of our lives. Our works of mercy give credibility to the Church’s proclamation of the mercy of God. It is in and through each of us that this mercy lives in the world. Our practice of mercy is an opportunity for us as the Diocese of Saint Cloud to grow more fully into the Body of Christ. It is the most fertile ground for the New Evangelization because in the Works of Mercy we tangibly and powerfully communicate the good news of Jesus Christ to the world.

I join Pope Francis in his confident hope that the Church of the Diocese of Saint Cloud, with the whole Catholic Church, “will be able to find in this Jubilee the joy of rediscovering and rendering fruitful God’s mercy with which we are all called to give comfort to every man and every woman of our time.” (12)May this Jubilee Year of Mercy be for all of us in the diocese an occasion for experiencing more deeply the bountiful mercy of God in our lives and of participating more fully in that mercy by showing it to all we meet.

Sincerely yours in Christ,

Bishop Donald J. Kettler

Saint Cloud, Minnesota

January 29, 2016

Endnotes:

1 Pope Francis, Misericordiae Vultus: Bull of Indiction of the Extraordinary of Mercy, 3. Hereafter MV.

2 The Church of Mercy: A Vision for the Church, p. 107. Hereafter CM.

3 “Homily on the Inauguration of the Jubilee of Mercy and the Opening of the Holy Door.”

4 Announcement of the Year of Jubilee.

5 Homily on Opening the Holy Door.

6 Letter of His Holiness Pope Francis According to which an Indulgence is granted to the Faithful on the Occasion of the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy.

7 Announcement of the Jubilee of Mercy.

8 Pope Francis, “Letter of Holy Father Francis to the President of the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelization at the Approach of the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy.”

9 Welcoming the Stanger among Us: Unity in Diversity (2000), Strangers No Longer: Together on the Journey of Hope (2003) and numerous recent statements of individual bishops and regional bishops conferences.

10 Laudato Si’: On Care for our Common Home, #115. Hereafter LS.

11 MV, 11; Dives in Misericordia, 2.

12 Announcement of the Year of Jubilee.