“Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century” by John Loughery and Blythe Randolph. Simon & Schuster (New York, 2020). 436 pp., $30.

By Mike Mastromatteo

There must have been more than a few raised eyebrows when in September 2015 Pope Francis, during his address to Congress, described Dorothy Day as one the greatest people of faith ever to come out of the United States.

With co-founder Peter Maurin, Day in 1933 set up the Catholic Worker Movement, the Catholic Worker newspaper and the first of a series of emergency shelters for the poorest of the poor of the Depression-ravaged streets of New York City.

Over the next nearly 50 years, Day would become an activist and gadfly to the rich and powerful, and she remains a paradox for many Catholics 40 years after her death in 1980.

Over the next nearly 50 years, Day would become an activist and gadfly to the rich and powerful, and she remains a paradox for many Catholics 40 years after her death in 1980.

A good deal of that mystery has been reconsidered in a new full-length biography, “Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century” by co-authors John Loughery and Blythe Randolph.

Day, who was received into the Catholic Church in 1928 at age 30, flirted with membership in the Communist Party in her youth, and later in life took pains to cloud over a somewhat hard-drinking, profligate lifestyle, which included affairs, arrests for taking part in protests and an abortion.

This new biography is more than a “warts and all” story of waywardness, conversion, dedication to the poor and hard-won redemption. The book also benefits from more of a sense of perspective than previous recountings of Day’s life and work.

Two earlier biographies, “Dorothy Day: A Biography” (1982) by William Miller and “Dorothy Day: A Radical Devotion” (1987) by Robert Coles, consist largely of verbatim tape-recorded interviews with their subject interspaced with author commentary. Both authors were former volunteers with the Catholic Worker Movement and personally familiar with Day during her lifetime.

A third memoir, “Dorothy Day: The World Will be Saved by Beauty” (2017) by Day’s granddaughter Kate Hennessy, comes across more as prayerlike inspiration than deeply researched exegesis and interpretation.

The Loughery-Randolph work meanwhile, has more to say about their subject’s legacy and its relevance to today’s believing Catholic or anyone concerned with the beatitudes.

Eschewing sentimentality and romanticism, Loughery and Randolph combine extensive research, wide reading and effective use of primary source material to shed more light on perhaps the most significant but controversial lay Catholic in 20th-century America.

Day’s involvement in protests, peace marches and picketing between 1917 and her last arrest in 1975, became a source of scandal and embarrassment to church leaders in her home New York Archdiocese. Owing however to the success of Day’s shelters and soup kitchens, especially during the Depression years, church leaders were loath to crack down on her efforts.

Oddly enough, had the then cardinal-archbishop of New York ordered Day to close up shop, she would have obeyed without hesitation. It was another of the many paradoxes in Day’s life story. Despite having a deep mistrust of all forms of authority, Day remained faithful and obedient to the church right down to the last letter.

Despite Day’s complete acceptance of the church magisterium, she was never entirely comfortable with a tepid practice of the faith. As authors Loughery and Randolph point out, “Dorothy Day in the war years could feel sickened by the state of American Catholicism — namely, priests and their parishioners who purported to love Christ but lived their faith in a perfunctory way, happy consumers and dutiful patriots, always asking too little of themselves.”

The authors suggest some naivete on Day’s part regarding her insistence on total pacifism, and her turning a blind eye to some of the worst abuses of communism. Nonetheless they extol her faith as unflinching effort to “live” the Beatitudes, knowing full well that hardship, suffering, rejection and loneliness would test her resolve every step of the way.

This new biography is useful to any Catholic — lay or ordained –– who would like to reconsider their personal practice of the faith. The story of Day’s struggle takes on increased relevance since March 2000 when the Vatican announced the case for her beatification, perhaps ultimately leading to her being named a saint.

“Dorothy Day asked hard questions,” the biographers conclude. “Her every statement, her every protest in the street, her lifelong rejection of comfort and respectability, ask: What kind of world do we really live in, and what sacrifices are we willing to achieve it? Do we believe our primary concerns should be our physical ease, our family’s and nation’s well-being, our happiness as individuals? Can a sense of the mystical thrive in a culture that has made sacred causes of the rights of the individual, material progress and technology? Is a flight from suffering and struggle a flight from God and an escape from the fulfillment of our deepest humanity? Day’s life suggests answers to those complex questions, though her answers offer little to please the skeptical, the covetous and the complacent.”

Mike Mastromatteo is a freelance writer in Toronto, who covers Catholic fiction for CNS.

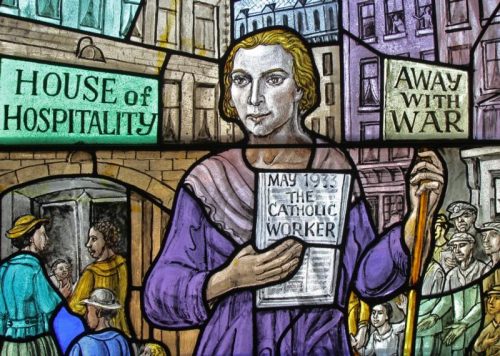

Feature photo: Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement and its newspaper, The Catholic Worker, is depicted in a stained-glass window at Our Lady of Lourdes Church in the Staten Island borough of New York. (CNS photo/Gregory A. Shemitz)