By Kurt Jensen

NEW YORK (CNS) — With a stronger point of view, the documentary “Spaceship Earth” (Neon), might have pointed out that its subject, the two-year experiment called Biosphere 2, never came close to producing anything in the way of enduring knowledge. Instead, it was a lot of ballyhoo abetted by sedulous and decidedly incurious news coverage.

Another way of looking at such a documentary during a time of sheltering in place might be: “And you think you’re bickering? How about getting locked into a gigantic greenhouse with strangers for two years, with people paying to gawk at you as though you were a zoo animal?”

Stressful, that.

The early 1990s come off like a quaint prelapsarian age before the internet democratized scholarship and when news came exclusively from network TV and print outlets. If a billionaire decided to fund a 140,000-square-foot sealed conservatory, it was treated with all the solemnity of a space shuttle launch.

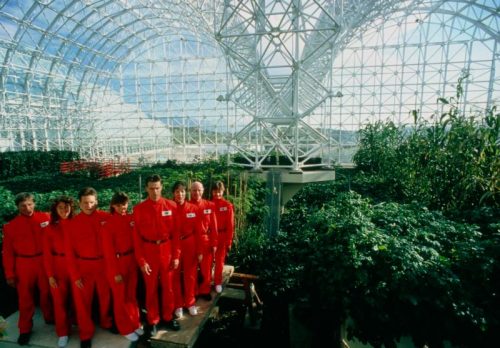

And if, as unlikely as it seems, someone managed to attract seven others willing to have themselves locked away there and could get them to mention that the place would be a combination of Noah’s Ark and the Garden of Eden, all the better.

Director Matt Wolf does the best he can with archival film, and his interviewees include John Allen, the sometimes-playwright who led the experiment, and a few of its “crew” members, many of whom saw Allen as a benevolent father figure. None appear to be angry or bitter about the experience.

Viewers don’t derive much knowledge of science from the film, other than the observation that its rigor requires experiments that can be duplicated under identical conditions. Meaning that another group would have had to lock themselves up for two years again.

Allen, a charismatic graduate of the Colorado School of Mines with a Harvard business degree, had a burgeoning interest in sustainable farming and ecology. He also had a knack for finding the financing for his ventures, which included an oceangoing exploration ship, the Heraclitus, and a self-sustaining commune in New Mexico, the Synergia Ranch.

His avocation was penning avant-garde plays under the nom de plume Johnny Dolphin, and some of his devoted followers were drawn from his casts.

Crew member Linda Leigh, a botanist, says the group “was a magnetic center. It just kind of pulled me in.” She’s also heard in a recording talking to her therapist: “I have a personal relationship with every single plant.”

Another member, Roy Wolford, was a doctor in his late 60s who promoted the belief that very low caloric intake could help you live to 120. (Wolford would die at 79.)

The publicized notion of Biosphere 2 was that it was a prototype of how a Mars settlement that generated its own oxygen might work. But there were also dark hints of survivalism and the belief, common during the Cold War years, that Western civilization could collapse, and biospheres would be the only way for a small elite to live in the aftermath of nuclear war.

Built north of Tucson, Arizona, the $150 million facility was financed by Texas oil billionaire Edward P. Bass. It exists still, operated by the University of Arizona as an environmental lab.

And what a utopia it was meant to be, with a manmade rain forest and savannah, a tiny ocean and a small farm with goats and chickens. It was also intended to be a showcase of water and nutrient recycling, and oxygen through photosynthesis, with 64 separate projects.

But it never worked as intended. As an ecological entertainment, certainly. As science, no.

The plant life never produced enough oxygen for human self-sufficiency, and carbon-dioxide levels grew so high that a scrubber had to be installed. Crew members feared brain damage and suffocation as a result. Wolford, moreover, was stretching out the low-cal meals, making everyone cranky.

No surprise, then, that there was intense bickering over farm chores, and the inhabitants sole pleasure became the making of banana wine, although they never had sugar.

The facility went into receivership in 1994 before the University of Arizona took it over.

Many viewers might see a lesson here in the folly of sealing yourself off, rather than encouraging activities and government policymaking to improve the environment of the planet — called Biosphere 1 here — we all share already.

But “Spaceship Earth” is more a chronicle of spectacle. It’s also a reminder that the 1990s may have been stranger than we usually recall.

A single expletive and oblique references to drug use make the film unsuitable for kids. But they are unlikely to be interested in its subject matter anyway.

For streaming information go to: https://neonrated.com/films/spaceship-earth#virtual-cinema.

Jensen is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.