By Christina Lee Knauss | Catholic News Service

An exhibit currently on display in Washington offers a moving portrait of the courage of Catholic journalists during the era of Soviet persecution in Eastern Europe, along with a potent message of faith and resistance to tyranny that has relevance in today’s world.

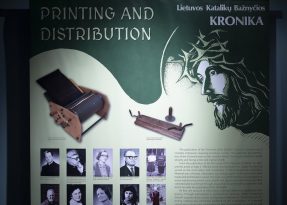

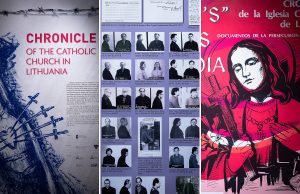

The Embassy of Lithuania is presenting an exhibit on “The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania,” currently on display in the Memorial Hall of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception through early September.

The Chronicle was founded 50 years ago in Lithuania, on March 19, 1972, and for 17 years it served as a way to get information about the conditions affecting the Catholic Church to people in the West.

When it closed in 1989, it was the longest-running “samizdat,” or clandestine, publication of its kind in during the era of Soviet control in Lithuania.

The Chronicle was founded by Father Sigitas Tamkevicius, who also edited it until his arrest in 1983. During its 17-year run, 16 others involved in producing the Chronicle also were arrested — a priest, four nuns and 11 laypeople.

The United States played a key role in spreading the word about conditions in the country. Issues of the Chronicle were smuggled out of Lithuania on microfilm and sent to New York City, where it was translated and circulated to a wide audience in the U.S.

During the Communist era, Catholics in Lithuania and in other East European nations suffered many atrocities. Churches were shut down, clergy were prohibited from practicing key elements of the faith, religious education was forbidden, and many priests and religious men and women were arrested and imprisoned.

“The church had very limited freedom to operate because the Soviet authorities tried to control it in almost every aspect,” said Jerry F. Powers, director of Catholic Peacebuilding Studies at the University of Notre Dame and former policy adviser at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Office of International Justice and Peace.

“They prohibited many church activities we take for granted like Catholic education, charitable activities, lay groups,” he told Catholic News Service. “It was so highly restricted that it was basically worship on Sundays and nothing else.”

Father Tamkevicius was put on trial after his arrest on charges of allegedly disseminating anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison and exile, serving some of those years in labor camps. He was exiled to Siberia in 1988 but was released the same year under the new Soviet policy of “perestroika,” or restructuring.

He returned to serving the church, first as spiritual director and then rector of the seminary of the Archdioceses of Kaunas, Lithuania. St. John Paul II named him auxiliary bishop of Kaunas May 8, 1991, then about two years later appointed him archbishop.

Pope Francis accepted Archbishop Tamkevicius’ resignation in 2015, when the prelate was 75. The pope elevated him to cardinal in 2019.

His memoirs about his years in prison were published earlier this year, but in a recent interview with CNS he showed no bitterness about his imprisonment. Instead, he expressed gratitude for his work at the Chronicle.

“When I started publishing, I expected I would be able to do the job for three years, but the Lord enabled me to do it for 11 years and the Chronicle definitely achieved its purpose,” Cardinal Tamkevicius said through an interpreter.

“In those days, saying the truth was very important and we played a role in unmasking Soviet lies,” he said. “We were able to demonstrate to people that they did not need to be so afraid, that they could be true to their faith and aim for a greater freedom.”

In this era when much mainstream media coverage in the U.S. seems to involve strident arguments about political issues, the Chronicle also offers an example of straightforward journalism untainted by opinion.

Its main strength was that it upheld a principle of avoiding ideological and political polemics and published only facts and information about events that were going on in Lithuania under the Soviets, said Arunas Streikus, a professor of humanities and history at Vilnius University in Lithuania.

“There was no commentary, no interpretation, just the facts of what acts the Soviet authorities were committing against the church and against citizens,” Streikus said.

Columnist and scholar George Weigel has followed the story of the Chronicle and written about it in his columns. He also worked in the late 1980s to set up ad hoc groups in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives to work on defending the rights of Catholics in Eastern Europe.

He said the Chronicle’s journalists and editors offer a moving example of people willing to take the ultimate risk in order to spread the truth of the faith.

“The legacy of the martyrs has always been important for the church as martyrs offer us the closest and most dramatic example of the imitation of Christ,” Weigel said. “Many of the people of the Chronicle were ‘martyrs’ in the sense of people who suffered greatly for the truth of Christ and the sake of his church, even if they didn’t die.”

Weigel also noted the Chronicle’s history offers an important lesson for Catholics today as they deal with both an increasingly secular society and, in some parts of the world, authoritarian regimes that threaten the autonomy of the church.

“The Chronicle teaches us to never give into tyranny,” he said. “Tyrants can’t stand the truth, and it’s an effective weapon against the evil of tyranny.”

Cardinal Tamkevicius hopes Catholics worldwide will realize how important it is to be able to freely worship God and take part in the sacraments. He said this is especially important in an era of rampant secularization worldwide and in light of events like the war in Ukraine.

“Freedom is a great gift from God, but it is easy to lose if you don’t fight for it,” he said. “The Chronicle is an example for all ages that even under very difficult conditions you can fight for your freedom.”

“In this day and age we also have to realize what a prize our faith is,” he added. “During the Soviet period, our faith was our greatest support, and I would hope going forward Catholics would realize our faith is our most precious gift.”