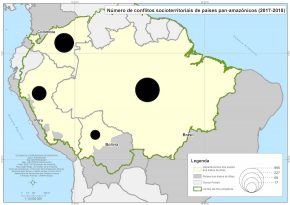

SAO PAULO (CNS) — The Brazilian bishops’ Pastoral Land Commission and seven other organizations launched the first Pan-Amazonian Socio-Territorial Conflict Atlas, showing the types and number of land conflicts which occurred between 2017-2018 in the Amazon region.

“There is very little information that crosses the borders of the Amazon. In Brazil, we don’t know what happens in Bolivia, nor in Peru or Colombia, and they don’t know what’s going on here, but the problems are similar,” said Josep Iborra Plans, a member of the Pastoral Land Commission’s Amazon articulation team. Plans participated in gathering data for the study.

The Atlas recorded more than 1,300 active conflicts during the years of 2017 and 2018 in the four countries, which cover 85% of the Pan-Amazon area. In all, struggles related to land disputes involved more than 167,500 Amazon families, the Atlas shows.

The Pastoral Land Commission said more than 100 researchers were involved in cataloging, among other issues, the number of conflicts, the type of groups or communities involved and the different causes of the dispute — whether for land or water, for control, for looting of natural resources, or due to problems of environmental contamination.

The Atlas shows different main causes for territorial conflict among the four countries surveyed. In Brazil, for example, agribusiness made up for 60% of the registered causes of conflicts, whereas in Peru, mining and extraction of oil and/or gas predominated conflicts, with 56% of the total conflicts registered.

In Bolivia, logging represented 43.2% of conflicts in the country’s Amazon communities, and in the Colombian Amazon, while planting illegal products remains an emblematic issue, the main cause of conflicts was the construction of infrastructure, such as roads, bridges and waterways.

“It is not the landless that cause most conflicts in the countryside. It is the aggressors of the squatters, indigenous people and traditional communities, wanting to take over their lands, waters and natural resources, who cause most of the conflicts in the Amazon,” said Plans.

The land commission said if it were not for the COVID-19 pandemic, the survey would have included data from 2019.

Plans said that in addition to the objective of increasing public opinion in favor of those who defend the forest, the Atlas also wants to “embarrass aggressors and hold authorities accountable for the defense and support of these populations.”

“The most suffering and resistant populations in the Amazon deserve to be seen and remembered in the defense of their territories, and supported in their struggles,” said Plans.

He said the situation in Brazil has worsened with President Jair Bolsonaro. The Bolsonaro administration, Plans said, has been systematically dismantling environmental protection, openly supporting the opening of mining operations in the region — including in indigenous territory — and facilitating land grabbing and illegal logging. In Bolivia, said Plans, after the coup that brought down former President Evo Morales, forest fires have worsened enormously.

“We need to help and unmask those unscrupulous people who, like Bolsonaro, try to hide their responsibility, accusing indigenous and caboclos (Brazilians of mixed ancestry) of burning.

During the Sept. 23 webinar to launch the Atlas, Bishop José Ionilton Lisboa de Oliveira of Itacoatiara, vice president of the Pastoral Land Commission, criticized remarks Bolsonaro made Sept. 22 in a prerecorded address to the U.N. General Assembly. Bolsonaro said indigenous peoples and caboclos were the main communities responsible for setting fire to the biome.

“We know that these words do not correspond to the truth,” said Bishop Oliveira.

“We see the trees, but it is difficult to see the forest,” said Plans. “This Atlas begins to prepare a Pan-Amazonian overview of the conflict situation in the field of rural communities. This helps to reinforce a more unified conception of a natural region torn by political boundaries, but with a similar problems.”

Besides the Pastoral Land Commission, the Atlas had the collaboration of the Research and Extension Group on Land and Territory in the Amazon (GRUTER) at the Federal University of Amapá; the Observatory of Democracy, Human Rights and Public Policies in Brazil; the Center of Investigation and Promotion of Peasants (CIPCA) and the National Federation of Peasant Women of Bartolina Sisa in Bolivia; the Institute of The Common Good in Peru; and the Minga Association and the University of The Amazon in Colombia.