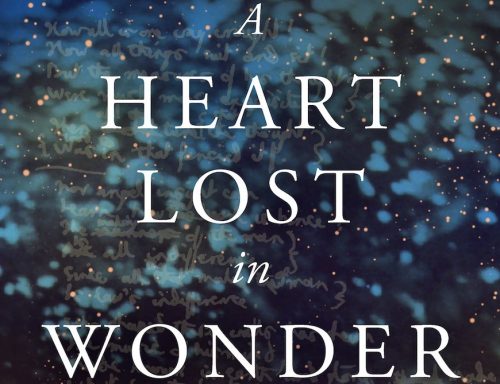

By Nancy L. Roberts | Catholic News Service

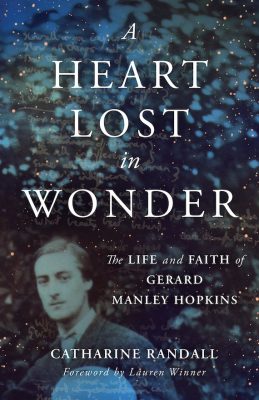

“A Heart Lost in Wonder: The Life and Faith of Gerard Manley Hopkins” by Catherine Randall. Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing (Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2020). 192 pp., $22.

Few poets writing in the English language are more beloved than Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889). This distinguished Victorian-era poet celebrated nature as divine creation, as in “Pied Beauty,” his poem inspired by the beauty of the Welsh countryside:

“Glory be to God for dappled things/For skies of couple-color as a brinded cow/For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim/Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings/Landscape plotted and pierced — fold, fallow and plough.”

Born into a high-church Anglican family, Hopkins studied classics at Balliol College at Oxford. In time, he joined the Catholic Church and became a Jesuit priest, which led to his estrangement from his family.

Hopkins was deeply troubled by the conflict he felt between his religious obligations and his passionate need to create poetry. In fact, he burned most of his poems and for many years stopped writing them entirely. He died of typhoid fever at age 44 and achieved posthumous acclaim as a poet through the efforts of his friend Robert Bridges, who later became poet laureate of the United Kingdom.

In this meticulously researched, readable biography, Catherine Randall, a scholar in residence at Dartmouth College, gives us a rich religious and literary interpretation of the poet’s life and work.

She tells us the diminutive, reclusive Jesuit, known for sometimes waving a bright red handkerchief to underscore what he was saying, “experienced great highs and lows, sudden epiphanies and conversions, dramatic changes of heart, periods of exultation and of abiding sorrow.”

She encourages us to consider “these quicksilver changes of mood” not as “a neurosis or a pathology,” but as “an innate constitutional response: simply who Gerard was, how he experienced the world, and how he apprehended God.”

Born into an artistic and even eccentric family, Hopkins developed an early love for sketching and music. He was particularly drawn to the pre-Raphaelite painters such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the music of Dvorak and Purcell. He also was inspired by Durer, Tennyson and Keats. Drawn to the natural world from a young age, he saw it as a direct revelation of the divine.

He found in the medieval theologian Duns Scotus an affirmation of the idea “that the grandeur of God, before which he was rapt, ‘all lost in wonder,’ could be concealed in the tiniest particle of nature.”

Too, Hopkins found God in human suffering and despair, including his own. Toward the end of his life, isolated and worn down by living in industrial Dublin where as a professor he was tasked with correcting reams of undergraduate papers, he sank into depression and alienation.

Eventually, though, he came to understand that God had allowed his suffering as a kind of “refiner’s fire … his short, intense life compressed like a brilliant, compacted diamond,” as Randall so aptly writes.

His happiest years, she observes, were those he spent in Wales at St. Beuno’s in Denbighshire, 1874-1877. He studied the Welsh language, which inspired some of his own experiments in writing verse, which he resumed at this time. In fact, Randall notes, about one-third of “his most renowned poems” were written during his sojourn in Wales.

They include “The Caged Skylark,” in which the lark represents Hopkins’ own soul. As she observes, the poem describes his “yearning to extricate the soul from a material ‘prison’ so that it may fly to its ‘own nest,’ as the soul will be homed to God in the resurrection, when it leaves its ‘bone-house’ and, like a rainbow on ‘meadow-down,’ is transmuted into light, leaving earthly substance behind.”

Typically, Hopkins’ poems begin with a depiction of natural beauty that links them directly to the divine. “The Windhover,” considered one of his greatest poems, starts this way:

“I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-/dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding/Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding/High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing/In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing.”

Hopkins’ is thus a sacramental view of nature, Randall writes. For example, when Hopkins is struck by the beauty of a bluebell he finds growing in a meadow, he asserts: “I know the beauty of our Lord by it.”

Randall shows how Hopkins “develops a profoundly sacramental understanding of God in Christ and of Christ in matter, in primal matter and motion even before the world began, in a way that anticipates the radical ‘environmental’ theology of Teilhard de Chardin.”

Randall delved deeply into Hopkins’ poetry and other writings and the correspondence between him and his friends, associates and mentors, as well as his extant journals.

The result is a thoroughly researched, illuminating portrait that helps us grasp the religious and literary context of Hopkins’ life and work. It is particularly welcome at this time, with the 2018 bequest to Oxford’s Bodleian Library by Robert Bridges’ grandson of 74 of Hopkins’ poems, thought to have been lost or even destroyed.

Anyone seeking to understand Hopkins’ poetry, particularly its deep spiritual depth, will find “A Heart Lost in Wonder” indispensable.

Roberts is a professor of journalism at the State University of New York at Albany who has written/co-edited two books about Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker.