‘I believe in God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible.’

Those opening words of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed are some 1,700 years old. While I cannot know just what our ancestors in faith intended by “all things visible and invisible,” it likely refers to both the material (those things accessible to the senses) and the spiritual (angelic beings that lack bodies and direct apprehension but known to faith).

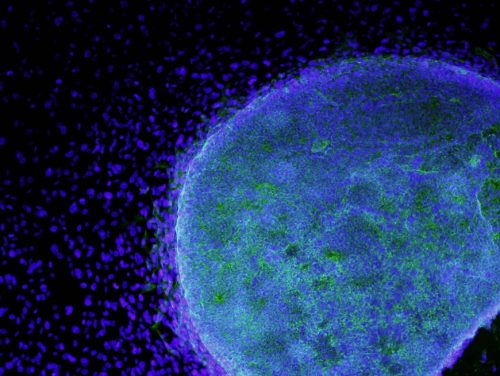

What is certain is that our age knows of the existence of invisible things our forebears could not have imagined with any clarity. The range of chemical elements; the molecular, atomic and subatomic structures of matter; black holes and unfathomably distant galaxies; the cellular basis of living bodies, bacteria, and viruses — these are among the “invisible” beings also created by the same God. And we constantly discover more.

These invisible things are on my mind of late as I read Siddhartha Mukherjee’s 2016 bestseller “The Gene: An Intimate History.” Rereading it, actually, and still intergalactically far from understanding all the science. It is a deeply engaging review of what we know about genetics, and how we got here; and most of all, how little we really know.

Every cell of your body has the same unique and unrepeatable DNA coding that both defines our common humanity and yet makes every human utterly unique. In its tightly coiled, microscopic invisibility are contained just four fundamental chemical compounds arranged in 3.2 billion “letters.” They encode 20,687 genes in the human body, which is 12,000 fewer genes than corn, 25,000 fewer than rice or wheat. It’s humbling to think that your bowl of cereal is more genetically complex than you are. Yet the potency of that relatively small number of genes controls every organic function of your body. It links you back across all human history and shapes the biological future of all human progeny to follow.

It is incessantly copying itself in your cells, repairing glitches in that copying, turning on just the exactly necessary proteins that control what happens in your body and differentiating cells, tissues, and organs that share the same “alphabet” but write very different cellular stories with it. Mukherjee includes no faith perspectives in his book but does state categorically that the embryo already contains the entire genetic blueprint of the human being.

Ninety-eight percent of DNA remains mysterious. Mukherjee states: “If the [human] genome were a line stretching across the Atlantic Ocean between North America and Europe, genes would be occasional specks of land strewn across long, dark tracts of water. Laid end to end, these specks would be no longer than … a train line across the city of Tokyo” (p. 324).

All of this gives deeper context to the awe enshrined in Psalm 139:13-14: “You formed my inmost being; you knit me in my mother’s womb. I praise you, so wonderfully you made me; wonderful are your works!”

Stunning as human genetics is to ponder, there is more to us. We are incomprehensibly complex matter, yes; but our human greatness does not reside in genes. It arises from being given by God an immortal soul united to the body. Science can study the effects of this soul, but it can never directly observe it. It is a “thing invisible” not because it is too tiny or too distant, but because it transcends matter as eternal spirit.

Why such technical topics for January? Each year we remember the anniversary of Roe v. Wade that legalized abortion. While that decision was reversed and the legality of abortion was returned to state legislation, the tragic loss of unborn life continues and the erosion of respect for human life across its spectrum of age and condition expands.

“The Gene” also recounts the history of eugenics, attempts to perfect the human race by eliminating the “undesirables” — originally by sterilization and ultimately by mass extermination. This, Mukherjee warns, is what knowledge decoupled from wisdom, reverence and humility can do.

Contrast eugenic tragedies with Jeremiah the prophet’s vision for the redemption of God’s people. This promise foresaw gathering a restored community together, with the blind and the lame in their midst (Jeremiah 31:7-9).

In faith, we await the endless day when there will be no more hunger or thirst, weakness or disability, sickness or death. But while we are on the way to that promised life, the blind and the lame are to be in our midst — every life in its magnificence and its fragility valued, protected, loved. It was a challenge then; it is a challenge now, but a challenge that calls out from us the best that we can be.

Though the life of a child in the womb is a “thing invisible” to the human eye, that life is cocreated with God, body and soul. It is how we each began. With each wholly unique person we see … and those we do not see … we rightly say with awe:

“I praise you, so wonderfully you made me; wonderful are your works, O Lord!

—

Feature photo courtesy of OSV News.