It’s not uncommon for the St. Cloud Diocese to receive generous donations in appreciation for the TV Mass, especially since the pandemic. But this one arrived with a powerful story. Anatol and Barbara Maciejny, who live in Northeast Minneapolis, are originally from Poland and experienced life under Communism during which practicing their Catholic religion was forbidden.

This is how Anatol told his story to Nikki Rajala:

In early September 1939, the war started in Poland. My father, Jozef, was in the Polish Army reserves on a troop train sent to fight the Nazis. He was one of 13 soldiers killed when German planes shot at the train.

Russian soldiers came to Poland to help, supposedly to fight Nazis, so we welcomed them with open arms. Instead they lined up people — the educated or military or Church members or landowners — and shipped us off. We didn’t know where we were going.

My sister, Marisia, was just a year old and I was 5 when soldiers forced my mother, Helena, and us to the train station in the next town. We waited there for several days, packed like sardines in a box car without food or water. Among those in our box car were Mother’s older brother, Jozef, his wife and their daughter, Czesia, four years older than me.

Mother’s sister, who wasn’t being forced to leave, took a chance and walked near the box cars, calling for Mother, “Hella, Hella?” When Mother heard her, she squeezed my baby sister out, hoping my aunt could care for her. With the butt of his rifle, a Russian soldier knocked my aunt to the ground. Still she and Marisia got away safely.

It took nearly three weeks to arrive at the work camp in Siberia where we lived from 1940 to 1943. Everyone had jobs, though I was too young. Mother was assigned to feed, milk and care for cows. Others were marched off to the forest to cut trees for lumber. Each healthy person had to cut down a certain number of trees and stack it like cordwood, even Mother. At the end of the day, we were given a loaf of bread and a bowl of soup. When people were sick and unable to work, if they had no family to take over their jobs, they starved to death.

Everyone was forced to speak Russian, so we learned enough to get by. Children were taken to a room with a picture of Stalin and commanded to bow to him as the supreme leader. They also attempted to erase our Catholic religion. Even so, people got together to pray when they were not being watched, and Mother continued private prayer. It was a grim existence for two and a half years.

Released without papers

Then, in 1943, after the United States signed a treaty with Russia, the soldiers had to release all “political prisoners.” They opened the gate and told us we could leave. Of course, we had no papers or money. I was about 8 years old.

With my uncle, aunt and Czesia, we hopped on trains and barges. It was wartime, so trains were full of military personnel and could kick us off. In the southern Soviet Union, we stopped at a cold train station where Mother and her new baby were told they could sleep on the warm station floor, assured that the train wouldn’t leave until the next day. When she awoke, our train had left — without them. It was a terrible time for Mother and the baby. At that time, they were forming a Polish Army in exile, so she joined the nurse corps.

On the shores of the Caspian Sea, my aunt and uncle heard that orphan children were allotted more food and signed me up for an orphan children’s group. Over the next eight months, we traveled to many different places in the Soviet Union, hungry all the time.

When Mother found cousin Czesia, she learned I’d been shipped to Iran just the day before. After her commander released her, she took the next ship to Iran. When she found me — nearly eight months after being separated — I was starving, barely skin and bones, with a distended stomach.

Being in the nurse corps, she located two cans of sweetened condensed milk and a Coca Cola, allowing me only a sip of milk and a half-swallow of Coca Cola at a time. That was hard because they were so delicious. Mother got me admitted to a British military hospital north of Tehran, where a doctor told her I wouldn’t live more than 10 days. It took several weeks for me to recover enough to leave the hospital.

From there we went from one refugee camp to another. By the middle of 1945, we were headed toward Syria in a truck packed with people and bags hanging all over. Somewhere in a remote area, our truck stopped — other trucks were blowing their horns and people were screaming. We wondered what was going on. They yelled, “The war in Europe is over!” It was May 8, 1945.

Refugees

We ended up in Lebanon, renting rooms in private homes, moving occasionally. At 10 years old I finally was enrolled in one- and two-room schools, studying Latin and French. Here we also regularly attended Mass in Latin. I served at those Masses, and still recall the Latin responses.

Mother was offered places to immigrate to: Africa, Australia, Poland. Because our home area was now part of the Soviet Union, I didn’t want to return — I remembered what Communism was like in Siberia.

Her two older sisters had immigrated to the U.S. before she was born — Anna to Minneapolis and Sister Maria Adultina to Chicago. Through the Red Cross, they arranged our passage from Beirut to the United States.

We traveled on a cargo ship in a private cabin on the top deck, eating with the officers, visiting Naples and other cities — it felt like first-class, given what we’d lived through. For the next three weeks, we stopped in every port on the Mediterranean. Finally, in Lisbon, our ship crossed the Atlantic Ocean, another 10 days. The captain taught me English words to greet my cousins and aunt. But before leaving the ship, I learned what those words actually meant — and not to say them.

The train trip to Minnesota took three days, stopping first in Chicago to visit briefly with Sister Maria Adultina before arriving in Minneapolis. My aunt Anna and her family met us at the train station, the first time these blood sisters ever saw each other.

Though I was almost 16, I was placed in eighth grade at Holy Cross School and switched to public school for ninth grade. From 1955 to 1957, I served in the United States Army as a meteorologist in Korea.

It wasn’t until 1957 when we were able to get my sister, Marisia, to Minnesota. She still lives here. My uncle Josef volunteered for the Polish Army in exile and fought at Monte Casino, Italy. He and my aunt immigrated to Toronto, Canada, where cousin Czesia still lives.

In Minneapolis, we attend Holy Cross Church, which had a Polish Mass every Sunday — before COVID. Some years ago, it was combined with several other parishes into a regional parish.

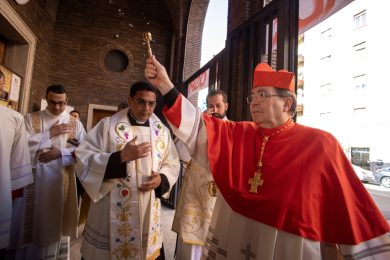

My wife Barbara, who also emigrated from Poland, prefers the Mass on EWTN, a high Mass with more singing. But I like to concentrate on the readings and the priest’s homily, which I can do better with the TV Masses from the dioceses of St. Cloud and Winona/Rochester. These last two years, we’ve enjoyed those TV Masses so much I wanted to support them. We sent both a check.

////////////

LEARN MORE: For more information or to give a gift to the Bishop’s Annual Appeal, visit www.stcdio.org/annualappeal.