VATICAN CITY (CNS) — Pope Francis’ visit to Egypt, a land increasingly marked by terrorist-led bloodshed, stands as part of his mission to inspire and encourage today’s actors in theaters of violence to change the script and set a new stage.

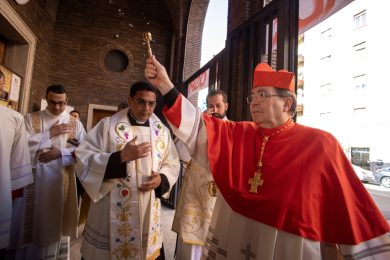

Just as the pope did when he raised the curtain of the Year of Mercy in war-torn Central African Republic, he goes to strengthen and “confirm his brothers of the Coptic Catholic Church and other churches present in Egypt,” said Cardinal Leonardo Sandri, prefect of the Congregation for Eastern Churches.

He will be able to show, in person, his support and solidarity for the beleaguered Christian minorities who continue to be targeted by terrorist fanatics and increasingly feel vulnerable and unsafe in their own land, said Maryknoll Father Douglas May, who worked in Egypt for two decades.

Even though Christianity there traces its roots to the times of the apostles, being a Christian in Egypt today “is like being black in the United States before civil rights or being a Jew in Germany before Hitler. You’re tolerated. But people don’t want to be tolerated, they want to be accepted as citizens with equal rights and equal possibilities,” said the 67-year-old priest, who grew up near Buffalo, New York.

To make things even more difficult, there is “still a very low level of ecumenical spirit” among many priests and bishops of the different Christian communities, even though laypeople already have a sense “that everybody is one: Protestants, Catholic and Orthodox.”

Church leadership “worries about who’s what” Christian denomination, he said. But when Pope Francis goes to Cairo April 28-29 to embrace Coptic Orthodox Pope Tawadros II, Christians will see “that we are all one family, even though we might have different last names,” he told Catholic News Service April 20 by phone from a small village in Upper Egypt.

“I think the biggest thing” that will come from the trip, he said, is Pope Francis “will affirm that there is a certain solidarity among Christians” and that “we are all related together by Jesus.”

An official visit by the Roman pontiff — the second in history — will bolster lay Catholics, he said, just like St. John Paul II’s landmark trip in 2000 did.

Many Catholics feel mistreated or maligned, he said; they often are seen as “heretics” by biased Orthodox and “referred to as infidels or idol worshippers” by prejudiced Muslims.

But “when John Paul came, it was the first time a Catholic could be proud and excited to be a Catholic and a Christian at the same time,” said the priest, who was in Egypt at the time. That joyful pride should be “the biggest impact” Pope Francis will make.

Archbishop Michael Fitzgerald, former nuncio to Egypt and past president of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, said the Catholic presence “is both enriched and weakened by the fact of being made up of seven distinct churches: Coptic Catholic, Melkite, Maronite, Syrian Catholic, Armenian Catholic, Chaldean and Latin.”

While that shows Catholicism’s rich diversity, it comes “at the price of a lack of cohesion,” he told CNS in an email response to questions.

Egypt has the largest Christian population in the Middle East, but the Roman Catholic Church is the country’s smallest, with about 250,000 members compared to the 9 million-10 million Coptic Orthodox, he wrote.

However, the presence of so many men’s and women’s religious congregations working in the fields of education, medical care and social work and the important and much respected work of Caritas Egypt mean the Catholic Church “punches over its weight,” said Archbishop Fitzgerald.

Father May spent many years doing priestly formation for the Coptic Catholic Church, and, in fact, he taught and was the spiritual director of Msgr. Yoannis Lahzi Gaid, one of the pope’s personal secretaries in Rome and the man who will be translating for the pope in Egypt.

Father May said he sought to teach the seminarians to leave the church walls, actively work in the risky world of social justice and be open to the help and goodwill of all people.

The impact on the Coptic Catholic priests he taught has been huge, he said. One of his many former students who are now paving new paths of interreligious and ecumenical initiatives powered by the participation of lay men and women, he said, is Father Boulos Nassif, whose work is featured in a Prison Fellowship International documentary titled “A Story of Friendship,” which can be found on YouTube.

Father Nassif founded the Hand in Hand prison ministry when Muslim families wanted the same kind of services and care he was offering Catholic and other Christian prisoners and their families. But fears of being accused of proselytizing led him to ask for help from the local sheik, Father May said, and now the two communities work together, not separately, which is highly unusual.

Father May said the problems facing Egypt’s Christians come from “several sources,” including al-Alzhar University, which is considered the world’s highest authority on Sunni Islam.

Many Christians feel “the voice from al-Alzhar is not strong enough against all this fanaticism, and it may even be affirming it,” he said.

The country’s huge economic difficulties and high unemployment also make minorities an easy target as “someone to blame,” he added.

“My hope is that Francis, with that smile of his, when he shakes hands” with the many dignitaries and religious leaders, all the negative baggage and attitudes “can maybe erode a little bit” and the whole nation can see what respect, dialogue and friendship look like.