By Cindy Wooden | Catholic News Service

KINSHASA, Congo (CNS) — In a country where most people are Christian and all are suffering from decades of violence and atrocities, Pope Francis told the Congolese to lay down their weapons and their rancor.

“That is what Christ wants. He wants to anoint us with his forgiveness, to give us peace and the courage to forgive others in turn — the courage to grant others a great amnesty of the heart,” the pope said in his homily Feb. 1 during a Mass on the vast field of Ndolo airport in Kinshasa.

Congolese authorities said more than 1 million people attended the Mass. They arrived as the sun began to rise, dressed up and carrying baskets of food. They sang and danced and prayed as they waited for the pope.

Many in the crowd, especially the women, wore cotton dresses with fabric printed specifically for the papal visit. One version featured the face of the pope wearing a miter. The other, with a more abstract design, had the logo of the papal trip and the theme — “All reconciled in Jesus Christ” — written in French, Kituba, Lingala and Swahili.

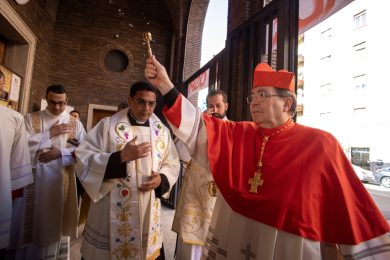

In his homily, Pope Francis spoke to the pain and suffering of the Congolese people, but most of the people in the crowd — like Father Slyvain, who was rushing to take his place among the concelebrants — said the joy of the pope visiting their country was all they cared about that morning.

The liturgy itself lent to the sense of joy. For the most part, it followed what commonly is called the Zairean Rite, using the “Roman Missal for the Dioceses of Zaire,” the former name of Congo.

The missal incorporates Congolese music and rhythmic dance, gives an important space to the litany of saints and of faith-filled ancestors, and the penitential rite and the exchange of peace take place together after the homily and before the offertory.

The Gospel at the Mass was St. John’s account of Jesus appearing to the disciples after the resurrection and telling them, “Peace be with you.”

Pope Francis pointed out how when the risen Jesus appeared to the disciples, he did not pretend that nothing traumatic had happened. In fact, “Jesus showed them his wounds.”

“Forgiveness is born from wounds,” the pope told them “It is born when our wounds do not leave scars of hatred but become the means by which we make room for others and accept their weaknesses.”

Jesus “knows your wounds; he knows the wounds of your country, your people, your land,” the pope said. “They are wounds that ache, continually infected by hatred and violence, while the medicine of justice and the balm of hope never seem to arrive.”

The first step toward healing, he said, must be asking God for forgiveness and for the strength to forgive others. It’s the only way to lighten the burden of pain and tame the desire for revenge.

To every Congolese Christian who has engaged in violence, “the Lord is telling you: ‘Lay down your weapons, embrace mercy,'” the pope said. “And to all the wounded and oppressed of this people, he is saying: ‘Do not be afraid to bury your wounds in mine.'”

Pope Francis asked people at the Mass to take the crucifixes from their necklaces or from their pockets, “take it between your hands and hold it close to your heart, in order to share your wounds with the wounds of Jesus.”

“Then,” he said, “when you return home, take the crucifix from the wall and embrace it. Give Christ the chance to heal your heart, hand your past over to him, along with all your fears and troubles.”

Another thing, he said, “Why not write those words of his on your walls, wear them on your clothing, and put them as a sign on your houses: ‘Peace be with you!’ Displaying these words will be a prophetic statement to your country, and a blessing of the Lord upon all whom you meet.”

Christians are called to be “missionaries of peace,” Pope Francis said. They are called to be witnesses of God’s love for all people, “not concerned with their own rights, but with those of the Gospel, which are fraternity, love and forgiveness.”