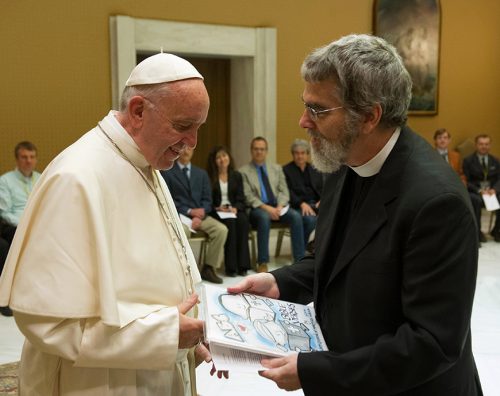

Each month, The Central Minnesota Catholic features a big question the Church is facing. July’s question is: “Are faith and science compatible?” Weighing in on this month’s topic are Jesuit Brother Guy Consolmagno, director of the Vatican Observatory and president of the Vatican Observatory Foundation; and Benedictine Abbot John Klassen, abbot of St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville.

A native of Detroit, Michigan, Brother Guy earned undergraduate and master’s degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a doctorate in planetary science from the University of Arizona; he was a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard and MIT, served in the Peace Corps (Kenya), and taught university physics at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania before entering the Jesuits in 1989.

A native of Detroit, Michigan, Brother Guy earned undergraduate and master’s degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a doctorate in planetary science from the University of Arizona; he was a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard and MIT, served in the Peace Corps (Kenya), and taught university physics at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania before entering the Jesuits in 1989.

Abbot John leads a community of 120 Benedictine monks who sponsor and work at St. John’s University, St. John’s Preparatory School, Liturgical Press as well as in parishes, hospitals and retirement centers, mostly in Minnesota. With a degree in bio-organic chemistry from The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., in 1985, he taught organic and biochemistry as well as an ethics course on technology at St. John’s University from 1983-2000 before being elected abbot.

Q: What is the Church’s historical relationship with science?

BROTHER GUY: In many ways, the Church invented science. Certainly, it has supported it throughout its history. This is a surprise to many people because there is such a “cottage industry” out there nowadays of people who manufacture this idea of a war between the two.

What was once called “natural philosophy” was developed at the medieval universities. Astronomy (what we would call cosmology today) was a required course for all students who wanted to continue on in theology or philosophy.

A number of the assumptions about the universe that are essential to doing science come specifically out of Christian theology: “reality,” that the physical universe is real, and not illusion; “causality,” that God is not a nature god making things happen by whim, but rather one who sets up laws that we humans can discern; and “value,” that the physical universe is good and an expression of a Creator, worthy of our study, because “since the beginning of time God has revealed himself in the things he has created” (Paul’s Letter to the Romans, 1:20).

One of the best bits of evidence of how the Church has supported science is just to appreciate how many devout Catholics — including many clergy — were instrumental in the development of science. In the early medieval period we can find Pope Sylvester II, St. Hildegard of Bingen, St. Albert the Great. At the beginning of modern science, Galileo himself was very Catholic (his two daughters were nuns), and Jesuit priests developed modern theories of optics, atoms and anthropology.

Much of the science published in the 18th and 19th centuries was done by the clergy; who else had the education and free time to collect and analyze scientific data? And today most people are familiar with the names Gregor Mendel or Louis Pasteur. Ampere and Volta (for whom amps and volts are named) and Avogadro were all devout Catholics. A number of Nobel Prize winners even to the present day are Catholic or otherwise deeply religious.

Modern support for science is found at the Vatican Observatory, in the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and at the thousands of Catholic schools and universities around the world where top-flight science is taught and pursued every day.

Q: Why does the Vatican have its own observatory?

BROTHER GUY: In 1582, Pope Gregory gathered astronomers to help him reform the calendar, and this work led to active mathematics and natural philosophy groups at the Roman College run by the Jesuits. They were early supporters of Galileo. Astronomy was supported by the Holy See, which was an independent nation, on and off for the next several hundred years. Finally, in 1891, Pope Leo XIII founded the modern Specola Vaticana to show the world that the Church supported science — at the time when the myth of this “warfare” between the two was first being invented.

Q: People who believe that the Church is not a friend of science often cite the Church’s response to Galileo. What is fact and what is fiction regarding the “Galileo affair”?

BROTHER GUY: There are hundreds of books, some better than others, that try to describe and explain the Galileo affair. (I wrote one of them myself!) They all disagree. At the very least, this should show that the issue is not settled even among historians.

Everything you think you know about the Galileo affair is probably wrong; alas, the truth doesn’t make the Church look any better. Galileo’s trial took place more than 20 years after his first book on astronomy, and 90 years after Copernicus had published the idea of the planets and Earth going around the Sun. Whatever the reasons for the trial — a combination of personal and political conflicts, probably — it was never a case of the Church trying to suppress science.

The idea that the Church was afraid of science, using Galileo as evidence, was invented during the 19th century for political reasons. For example, anti-immigrant forces in America at that time spread this tale to argue that “ignorant Catholic immigrants” from eastern and southern Europe should not be allowed into the country — people like my grandfather.

Q: What led you to your vocations — as a Jesuit brother and as an astronomer?

BROTHER GUY: My Italian father introduced me to astronomy, my Irish mother to my faith; my older brother, to science fiction! They all played a role.

In my Jesuit high school, I learned to “find God in all things,” and thus I realized that to be a good scientist was a great way to get to find God. I originally went off to Boston College, a Jesuit school, with the thought of being a Jesuit priest; but my prayer there told me strongly that God did not want me for the priesthood. Meanwhile, when I visited a high school friend at nearby MIT, I found they had a great science fiction collection, and so I transferred there, choosing to study “planetary sciences” because planets are places where people have adventures!

Twenty years later, after a doctorate, a full research career, and even time in the Peace Corps teaching astronomy in Kenya, I finally recognized that my call was to be a Jesuit brother, not a priest. I assumed they would assign me to a university, but instead I was ordered to go to Rome and join the Vatican Observatory. I had to obey!

Q: Some of the biggest “Big Questions” in science are in the field of cosmology. From your perspective as an astronomer and person of faith, how do theories about the beginning and ultimate fate of the universe enhance or challenge your faith?

BROTHER GUY: As you may know, the Big Bang theory that forms the basis for our cosmology today was developed by a priest-scientist from Belgium, Father Georges Lemaître. The expansion of the universe observed by [Edwin] Hubble was first predicted by him, and it is called the Hubble-Lemaître law. Father Lemaître was always careful to distinguish a difference between the event of the Big Bang as different from “creatio ex nihilo,” creation out of nothing.

God is not just some force who sets off the Big Bang. God’s creation occurs outside of space and time, and so it happens at every space and every time: It is the creation of space and time itself, and the creation of what we call the laws of nature that allow the Big Bang to occur. This will be true even if at some future time we come up with a better description than the Big Bang to explain what happened when the universe formed.

Q: How can faith and science both help us to understand our world and our place in it? Are they both seeking truth?

BROTHER GUY: More than truth, both science and faith are seeking understanding of the truth. I like to put it this way: In science, we are seeking to understand the truth about the universe. We can understand our human-made descriptions of the universe, but they are always only partially true. That’s why we keep doing more science, to make them ever closer to the truth.

In faith, we are given divine truths, but since we are not divine ourselves we only partially understand them. We say that we “practice” our faith because only practice makes perfect, and none of us are perfect yet. Science is understanding, seeking truth; faith is truth, seeking understanding.

Q: What are the biggest myths people believe about the Church and science?

ABBOT JOHN: I wish to situate my response to this question within the larger context of the Catholic intellectual tradition, of which science is one part.

From the earliest years of Christian mission, the disciples of Jesus faced the challenge of how to live faithfully and with integrity in the world in which they found themselves. They devoted great energy to thinking about how life in the Risen Lord could take root in the communities of the Greco-Roman world.

One of the earliest examples of this engagement with a different culture is St. Paul’s address to the Athenians at the Areopagus (Acts 17:22-32). Many generations of believers reflected deeply on how the message of the Gospel could interact with a variety of cultures, and they created a nuanced and resilient intellectual tradition. That tradition was marked by the capacity to adapt and transform methods of inquiry, ways of knowing, and educational processes that originated outside a Christian context — in Alexandria, Rome, and other intellectual centers.

Over the centuries, this intellectual tradition has become a powerful force for understanding and communicating the Christian message. It is also a touchstone for assessing new ideas. It sets its sights on the full development of virtues that make for a good life and that foster the common good. For example, Origen develops a rich sense of reading that one uses to deal with the complexities and seeming contradictions in the Scriptures. Athanasius, Basil, the two Gregorys and others help the Church come to a rich understanding of the humanity and divinity of Jesus. In the desert, Evagrius writes an account of the spiritual challenges the hermits faced in the desert and how they responded with the help of a spiritual companion. And the list goes on. The point is, the Church has always had a brain.

The Catholic intellectual tradition is a treasury of scriptural exegesis and catechesis, theology and spirituality, drama, literature, poetry and music, vast systems of philosophy and moral thought, as well as art, architecture, history and science.

This enormously rich tradition is built upon a few cornerstones put in place by the earliest Christian thinkers.

These cornerstones include a commitment to think seriously about the culture in which one lives, to attend with respect to the ideas and worldviews of others. These cornerstones include the commitment to listen to what God is speaking through them, and to use ideas old and new to understand the Gospel, and communicate it in changing times and places.

If I think that Genesis 1 is a historical, scientific statement about creation rather than a poetic, theological statement about God’s creative power in relationship to the creation, scientific conclusions will constantly erode my faith in the God and in the Church as presented in the Bible.

MYTH 1: The Bible is not doing science or history the way we do it. Rather, the Scriptures, in many different books are telling us about the loving fidelity of God for all of creation, who we are as humans in that creation, and how to live as humans with integrity and purpose.

MYTH 2: The creation is simple, utterly ordered, and there is no randomness in it. Rather, order and design live in dynamic relationship with randomness and disorder. If creation is something that happened “back there somewhere,” with divine involvement, but as a one-time event, most likely, my faith in God is probably shrinking and remote, or at least compartmentalized. As Teilhard suggested, God has to be more …, out in front of the creation, than at the back end somewhere.

MYTH 3: Creation is done, finished. Rather, creation continues to unfold all across the universe and on this earth. If I understand God as a designer, who lets the creation unfold for a while by its own natural processes, by the “rules” that are part of the physical universe, but then when the creation gets stuck, God has to step in and tinker, my understanding of God will be at the mercy of the latest scientific conclusions. Further, the Church and its teachers will be very reluctant to incorporate even rock solid conclusions into its theological teaching and reflection on doctrine.

MYTH 4: God is in complete control. Rather, God gives enormous freedom to the creation and to us as human beings. If we are not ultimately free to choose between good and evil, we have lost an essential element of human identity.

MYTH 5: Science is the only reliable way of knowing anything. Rather, it is one way, with a simple method, that when used properly, yields powerful results.

Q: Do Catholic universities like St. John’s and St. Ben’s have any special responsibility to address the relationship between faith and science? How does the Benedictine tradition view this?

ABBOT JOHN: As universities and in the Church, we need to be clear in teaching and preaching that asking tough, challenging questions of both scientists and theologians is perfectly wonderful. The structure of scientific knowledge will not fall apart in the face of curiosity and the desire to know, and neither will the tradition of faith in God. Overwrought certainty in any scientific field collapses into ideology, that is a structure of belief that will not tolerate questioning (how ironic!). Within the realm of faith, certitude takes one into dogmatism, an unquestioning certainty about parts of the tradition that no longer has a context. It is natural for human beings to be curious, to ask questions, to be searchers, to wonder. This is true in both a scientific and a religious context.

What does the life of Benedictine monasteries mean to our life as Catholic schools? Well, the reflective, prayerful reading of Scripture is one of the cornerstones of our spirituality. And it extends into everything we do as monastics in our praying and working. In our schools, in a culture that is losing its ability to read mindfully and carefully, we may not give up on reading: literature, poetry, political science, chemistry, biology, across the span of human learning and imagination. We need to be teaching and learning how to immerse ourselves in a text, truly understanding what it says, what it means, making connections, learning to love words, the way they sound, the way they feel in our mouths.

As learning environments, in a loud, fast moving, high-tech world we want to encourage the development of contemplative habits — of reading and studying. As Benedictine learning communities, we want to know experientially what “lectio divina” is.

I mean this in a large, rich sense. It means sitting with a text, whether that be the “Brothers Karamazov,” “War and Peace,” “Anna Karenina,” “Madame Bovary,” whether Genesis, the Gospels of Luke and Mark, Acts of the Apostles, Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” or “King Lear,” the poets Mary Oliver or Wendell Berry; whether it is the text of a wetlands or prairie, the text of a rough section of an inner city; the text of data from spectroscopy or a mass spectrum; the text of a film such as “Twelve Years as a Slave” or “No Country for Old Men” or “Gravity.”

Reading in this way is a generalized way to make connections between different ways of knowing and believing.

I think that the Church has to help its members be aware of fundamentalism in all of its many guises, whether in reading the Scriptures or the doctrine of the Church. The Bible is not one book, it is many books, and one has to read each one in a way that is suitable to its genre, just as one reads St. Augustine’s “Confessions” in a different way than “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain. Why was Genesis 1-11 written? Is it really a scientific, historical account of the early days of creation? What kinds of stories are these? What do they mean for us today? Or the Book of Jonah, or the prophecies of Isaiah? What is the purpose of any Church doctrine? Where did it come from? What does it mean? How does it fit into the bigger picture? Why does it matter for our faith?

/////////////////////

Minnesota Catholic Podcasts

Minnesota Catholic Podcasts

JULY 2020

The following podcast will be posted in July. You can access it by visiting www.TheCentralMinnesotaCatholic.org and clicking on “Minnesota Catholic Podcasts.” You also can subscribe to Minnesota Catholic Podcasts on iTunes or Google Play.

Topic: ‘Hobby astronomer’ priest keeps his eye on the heavens

Guests: Father James Kurzynski, pastor of St. Olaf in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, is an amateur astronomer who contributes to the Vatican Observatory Foundation’s “Sacred Space Astronomy” blog. Father Kurzynski discusses his priesthood vocation, how he became interested in astronomy and his views on the relationship between faith and science.

/////////////////////

Question for reflection

In a recent document titled “Outreach to the Unaffiliated,” the U.S. bishops’ Committee on Evangelization and Catechesis noted that many people who leave the Church “consider faith and religion to be incompatible with science and rational thinking.” What is something that we as a Church can do to effectively address this challenge?

You are invited to submit your answer (150 words or less) to editor Joe Towalski at jtowalski@gw.stcdio. org. A sampling of answers will be published in a future edition of The Central Minnesota Catholic.