This story happened many years ago. Some of the principal actors in this story are dead.

My husband was the director of Catholic Social Services in the archdiocese where we then lived.

We were attending a social event, and a Catholic woman who had long served as a foster mom both for the state and the Catholic agency approached my husband. Helen had taken care of a multitude of babies, many of whom were on their way to adoption. But now she had a problem.

She was caring for a tiny baby who had hydrocephalus, a buildup of fluid around the brain. Today, early treatment often results in a long life span, but this baby had many profound issues, and Helen was concerned about his survival. She wanted him baptized.

She had approached her pastor, a monsignor, who told her that much paperwork would be involved. The mother, who had abandoned the child but not legally relinquished, would have to be located to give consent.

In general, this is a good rule. Initiating someone into a religious group is a parent’s right. But in this case, that presented a bureaucratic and logistical nightmare, if not an impossibility. The baby, Helen felt, needed to be baptized now.

My husband said, “Let’s ask Steve,” pointing across the room toward the priest who would soon be the vicar general for the archdiocese. He was also, like us, a former Jesuit volunteer, and a good friend.

Steve didn’t hesitate.

“Bring the baby to the chancery on Friday,” he told Helen. There was a Mass for chancery employees every Friday, held in a small conference room and usually sparsely attended.

On Friday, I drove downtown for the baptism. The conference room was packed, the chancery community wanting to be part of this. Helen was the godmother, my husband the godfather.

My memories are vague. I don’t remember the baby’s name, and I don’t remember what happened to him later. Father Steve was a great homilist, but I don’t remember all that he said.

But what I do remember has lived with me for a long time.

“In the eyes of the world,” Father Steve told us, “This child means nothing. But in the eyes of God and of our Church, this child is precious and valued.”

I do remember many people cried.

On my refrigerator hangs a card with the picture of Jakelin Caal Maquin, who was 7 years old when she died of sepsis after being taken into U.S. custody following her journey from her native Guatemala. Many times, cleaning up, I’ve thought about tossing the picture in recycling. But I can’t, because Steve’s words linger. In the eyes of the world, this child meant nothing.

But to us, Jakelin is precious. So are those considering the tragedy of abortion because they have no access to good health care for themselves and their babies. Precious are those on death row, and the homeless, so prevalent in a country where some of the wealthiest pay little or no tax. Precious are those who feel unwelcome because they are LGBT.

If we, the Church, follow Jesus, these should be our concerns.

Jesus lived at the margins with lepers, prostitutes, tax collectors, the woman a bunch of self-righteous men wanted to stone. He died between two thieves. Jesus, like Father Steve, wanted us to understand that God’s plan for the kingdom on earth, the beloved community, ran counter to so much of what the world promotes and values.

With Jesus, we attempt to stand at the margins with the abandoned, the unwanted, the desperate and the unwelcomed.

Effie Caldarola writes her column for Catholic News Service.

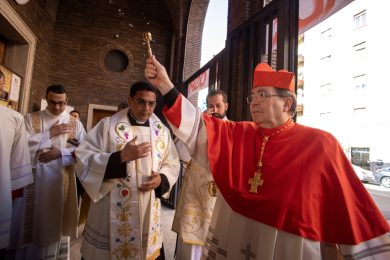

Top photo: Pope Francis embraces a person while greeting the diabled during his general audience in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican Jan. 27, 2016.