Note: The following article was first published in The Visitor in January 2015.

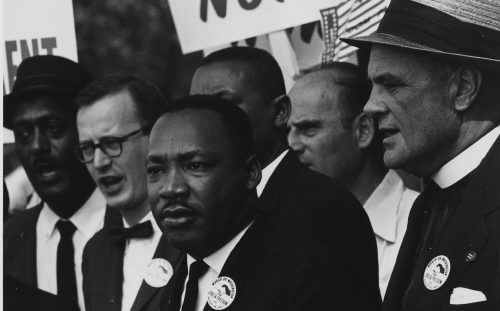

[Today,] the U.S. commemorates Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, honoring a man who, perhaps more than any other, is associated with the Civil Rights Movement and the push to end racial discrimination in this country.But the Rev. King’s vision of equality for all, no matter the color of their skin, would not have been possible without the hard work, commitment and sacrifice of so many others dedicated to the cause. One of those who shared King’s vision was a St. Cloud native, a Johnnie who was deeply motivated by his Catholic faith and who worked closely at times with King and his protégés.

His name was Mathew Ahmann, and in the late 1950s and 1960s he was at the heart of national Catholic efforts on behalf of racial harmony and equality.

Although Ahmann was one of nine speakers at the 1963 March on Washington where Rev. King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, he did most of his work behind the scenes. This might explain why, even here in his home Diocese of St. Cloud, many people aren’t familiar with him or his work. I didn’t know about him until a few days after he died on Dec. 31, 2001, when his obituary arrived at The Visitor office.

But the upcoming King holiday and the nationwide release of the movie “Selma” — about the 1965 civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., in which Ahmann also played a role — are opportunities to once again recall his life and legacy. This is true particularly at a time when race relations in the wake of events in Ferguson, New York City and other places around the country face new challenges.

Going to Selma

Paul Murray, a sociology professor at Siena College in Loudonville, N.Y., is a student of Catholic involvement in the Civil Rights Movement. He has been writing a series of profiles about individuals from that time, including one about Ahmann, who led the Chicago-based National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice from 1960 until 1968.

Murray calls Ahmann a “quiet crusader for civil rights” — a humble man who avoided the limelight, preferring instead to work for the cause behind the scenes.

Ahmann’s work in Selma is a good example of that.

On Sunday, March 7, 1965, hundreds of civil rights demonstrators set out to march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery. But as the marchers headed out of town across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they encountered a wall of state troopers determined to stop them. The troopers charged the crowd, beating and injuring many of the marchers.

In the wake of what became known as “Bloody Sunday,” Rev. King sent telegrams to the nation’s major religious denominations asking them to join him in Alabama for more marches and protests. Ahmann worked the phone that night and the next day urging priests and NCCIJ council members to answer the call.

Ahmann flew to Selma and settled in at the St. Elizabeth parish hall “where he followed a ‘monastic’ schedule, retiring each night at 2 a.m. and rising for Mass at 6:30,” Murray wrote. When someone suggested that the presence of Catholic sisters would discourage further violence in Selma, Ahmann invited them, too.

In the end, more than 900 Catholics participated in the protests thanks to Ahmann’s efforts, Murray said.

The impact of the events in Selma rippled far beyond Alabama. In the St. Cloud Diocese, Father Daniel Taufen, who was the editor of The Visitor at the time, wrote a lengthy editorial in the newspaper’s March 28, 1965, edition in support of the marchers’ ultimate goal.

“The ingrained prejudices of many of the people of Selma may seem to present an almost insurmountable obstacle, but the God who can move mountains can also move hearts,” he wrote.

He ended with these words: “What we are asked to do is to tear down the barriers we ourselves have raised which have kept the [African-American] from assuming his own rightful place in our society and country. Our job is to do something to ourselves, not to them.”

Grounded in faith

Ahmann was born in St. Cloud on Sept. 10, 1931. His father, Norbert, was a dentist and his mother, Clotilde Hall, was a nurse before she married.

The family was grounded in their Catholic faith and Ahmann always had a special concern for the marginalized. Murray relates a story about a time when Ahmann gathered with a group of young people that included a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany. When some children started to sing an anti-Semitic song, “Matt stopped it short in no uncertain terms.”

He attended St. John’s Prep and St. John’s University, where he became involved with the Young Christian Students association that applied an “observe, judge, act” approach to social issues. Pope Francis, known for his intense pastoral concern for the poor and vulnerable, uses the same approach, according to Cardinal Walter Kasper of Germany, who is preparing a book on the pope’s theology.

Ahmann graduated from SJU in 1952, and Murray says he remained rooted in the Benedictine values of community, hospitality, spirituality and respect for others.

Ahmann relied on those values as he worked to build support for the Civil Rights Movement within the Catholic community and his work in forming coalitions with other denominations and faiths to advance the cause.

The passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 was due in large part to the efforts of organized religion, Murray said, and there is a similar need today to mobilize churches and “bring together people from many different traditions” to address important issues around race relations that have garnered national attention in recent months.

In that vein, St. Cloud Bishop Donald Kettler, who recently met with leaders of the Central Minnesota Islamic Center following several acts of vandalism there, has voiced his commitment to bring together the area’s Christian and non-Christians faiths in ways that encourage dialogue, mutual understanding and working together whenever possible.

If Ahmann were alive today, he would surely support such efforts. His commitment to ending racial discrimination, peace and justice is a legacy that our nation and our world need to honor today.

Ahmann’s closing words at the March on Washington continue to serve as encouragement as well as a warning:

“Those of us gathered here before the Lincoln Memorial, and those of us gathered in witness around the nation, pledge ourselves that now is the time we respond to the demand of our conscience, now is the time we grasp the ideal our faiths and our Constitution hold before us,” he said. “There is no turning back. In a decade or less we will have done our utmost to have secured a community of justice and fraternity and love among us, or we will have laid the seeds of our own destruction.”