The following was published online Oct. 13 by America magazine, a national weekly Jesuit publication based in New York. It is offered here as a guest commentary.

Now that the church has gathered together reports from nearly all of the bishops’ conferences around the world, Pope Francis has declared the first phase of the church’s ,,, world Synod of Bishops on synodality over.

But that first phase of consultation with the faithful has been more than just an exercise in gathering information. It also has offered some valuable lessons. It will be crucial to keep these in mind during the synod’s second phase — meetings of “continental assemblies” from January to March 2023 — and then the third phase, the international assembly of bishops at a later date.

Three primary lessons will be most instructive in the coming year.

First, we have seen that shared governance of and responsibility for the church is possible, but it will require humility from all quarters.

Second, we do not know all the answers — and we may be surprised by some that may emerge from the process.

Finally, a lesson we have been taught many times but need to remember once again: Universality does not mean uniformity. To be universal is to respond to the missionary call of Christ; to be uniform is to stifle the Spirit Christ sent.

Any reading of the synod reports that emerged from the United States makes it clear that participants focused on priorities that are not always reflected in the actions or policies of the U.S. bishops.

To a certain degree, this is to be expected: The bishops are called upon to teach, sanctify and govern, and none of those three charisms is fulfilled simply by following the preferences of the majority or sailing according to the prevailing winds.

At the same time, when laypeople — who are, after all, the vast majority of the members of the church — come to different conclusions about priorities on which the church should focus, can we see this as an example of the people exercising a teaching charism? The synod reports are a way for participants to impart their own wisdom to leaders whose governance might be improved by listening and learning.

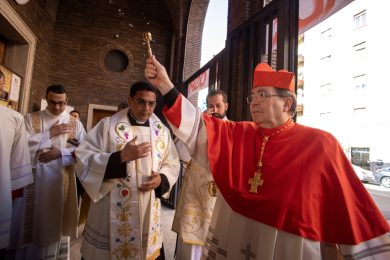

In many cases, such listening can be enriched by learning tools that are already available. The churches in Africa, for example, have fully embraced the process, according to Cardinal Mario Grech, the general secretary of the synod.

“They’re saying, ‘Listen, it has been such a very interesting ecclesial experience, we would like to proceed, to go forth,'” the cardinal told America magazine. In South Africa, the church has begun addressing families that are broken. In Asia, participants have recognized that the lack of synodality is not limited to the church, but also includes the family. Laypeople are eager to accept responsibility for leading the church.

There is no way to be certain of the outcome of a process like a worldwide synod. Participants must be willing to be surprised, disappointed or even chastened by some of the feedback that comes out of local and regional deliberations.

In the United States, for example, it was clear from press reports after the initial release of the synod synthesis documents in September that some church officials and bishops were surprised at the level of rancor and discontent to be found in the documents. Not enough, some felt, was made of all the good the church does.

It may be true that we all need to be more attentive to good news, to be more cognizant of the ways in which all the good present in the church (and all the good the church does) can be used to uplift us all. But the synod is meant to be a genuine deliberative process, not an exercise in public relations.

We should not be surprised when any notion of the church as a “societas perfecta” is not embraced by people who have real wounds and struggles. Will we be able to listen if large swaths of the church urge change on issues like married priests, LGBT ministries, women’s sacramental charisms and more?

Can laypeople embrace the uncertainty that may come when questioning their leaders in the synodal process? Will church leaders not only listen to young Catholics when they participate but also allow them to lead and implement their ideas? Will they listen if the perpetuation of clericalism in all its forms turns out to be an object of worldwide lament?

We all have a version of what “the church” is, and for most of us that concept is reified in our local congregation or diocese. But of course, the church is much bigger than any local community.

Since the days of St. Paul, the church has been diverse in composition and in gifts. It makes sense that the synod reports from around the globe reflect a church that is far from uniform in its priorities and concerns. It may be that even the continental assemblies will express different desires and concerns. But this is not a design flaw; it is an opportunity.

It would be disastrous for our global communion if any group in the church sought to attain a uniform, one-size-fits-all result from the synod process. This is not a fourth-century campaign to drive Arianism from the church, nor should it be a vehicle to impose our own ideological blinders on the eyes of everyone.

This is an especially important lesson for Catholics from North America and Europe — long accustomed to having the dominant voice in the church — to remember in the coming year. The Amazon and the Nile flow into the Tiber just as much as the Rhine does.

We cannot tell what fruits the synod process will bear in the end; there is always the possibility that we will not recognize them for decades to come. But throughout this process, the church must remember Jesus’ promise to send an advocate to be with us always (Jn 14:16).

It is that promise that Pope Francis has time and again reminded us of during this process. It is the Holy Spirit — and not any subcategory of the church — that is the protagonist in the global synod. “The Holy Spirit guides us where God wants us to be, not to where our own ideas and personal tastes would lead us,” Pope Francis said as the synod began. “Without the Spirit, there is no synod.”

The synod is far from over, and our journey together has only just begun. May we, as Pope Francis calls us to do, place our trust in the Holy Spirit, who is now and always will be our advocate and guide.