By Eugene J. Fisher

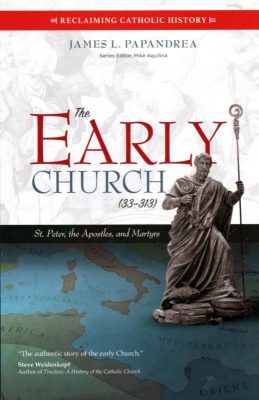

“The Early Church (33-313): St. Peter, the Apostles and Martyrs” by James L. Papandrea. Ave Maria Press (Notre Dame, Indiana, 2019). 125 pp., $16.95.

“The Early Church” is the first in a series of books on “Reclaiming Catholic History.” The seven books in the series will recreate for general readers the experiences and development of the church through the periods of the Roman Empire, the Dark and Middle Ages, the Reformation, the Enlightenment and into modern times.

Judging from the quality and readability of this initial effort the series should prove to be a great help to Catholics interested in understanding the development of church doctrine, theology, philosophy and responses to changes in society throughout the centuries.

James Papandrea, a historian and biblical scholar, dispels common myths and misconceptions about the history of the church over its first three centuries, replacing them with an objective understanding of the challenges faced by the Jesus movement as it evolved into the church we know today. In each chapter, beginning with the apostles and their immediate successors, he centers his narrative on specific individuals, allowing for engrossing narratives with which the reader can personally relate.

St. Stephen and Pope Clement of Rome are featured in the first chapter. In each chapter, Papandrea asks questions of the reader under the rubric “you be the judge.” In Chapter 1, the first question is “Were Christian holidays originally pagan holidays?” The answer, of course, is no. They were originally Jewish holy days, reflecting the continuity between the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament, and between Judaism and its younger sibling, Christianity.

He also narrates the development of the Catholic doctrine that Jesus was/is both fully human and fully divine, pointing out the people who believed Jesus was one or the other but not both and the early theologians who worked to clarify the central doctrine of the church, the Incarnation. The Incarnation, I might add, is the one that distinguished the early Christian community from the Jewish community, since many Jews felt (and still do) that this doctrine blends the necessary distinction between humanity and divinity and might lead its believers into some form of idolatry (worshipping a human as if he or she is a god or goddess).

Chapter 2 presents Ignatius of Antioch and Polycarp of Smyrna, asking readers whether “all” sin is equal in the eyes of God. (Again, no). The book then narrates the era of the apologists, centering on Justin Martyr and the martyrs of Lyons and Vienne in France, and the veneration of Christian martyrs and saints who serve as models for believers to this day. He is careful, as an historian, to distinguish between what we know about their lives and deaths and the myths and stories that developed around them.

Here, he asks readers to judge whether the Christian faith was “ruined” by being told in terms drawn from Greek philosophy (no) and whether when we die only our souls go to heaven (no, like the risen Jesus we will be saved for all eternity, body and soul).

The concluding chapters, written in the same format, take up the eras of the theologians, the development of the sacraments as we know them, and the era of Roman persecution of Christian and Christian “tribulation,” dispelling myths, for example, about the real use by Christians of the catacombs under Rome. His final note, of course, is titled “Just the Beginning.” And it is. Catholic readers will look forward to reading the rest of this series after such a fine beginning.

Fisher is a professor of theology at St. Leo University in Florida.