WASHINGTON (CNS) — An estimated 100,000 apprehensions of immigrants by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol agents at the U.S.-Mexico border in March is the highest figure in one month in a decade.

But there is more than just those raw numbers, or President Donald Trump’s action to cut $500 million in aid to three Central American countries, or his since-revoked threat to close the border with Mexico.

What’s missing, many say, is the human element of immigration.

“They are mothers and fathers just like us and they are trying to do the best they can for their children and their families, just as we would,” Joan Rosenhauer, head of Jesuit Refugee Service, told Catholic News Service April 4 — the organization’s “lobby day” during which they talked to 41 members of Congress and their staff.

“People don’t leave their homes, their families, everything they’ve ever known, for fun,” Rosenhauer said. “People are invested in their situations and try to keep their children from harm, which is what people in the U.S. would do.”

She added, “We can’t back away from all this. We can’t step down from serving millions and millions of children who have bene traumatized — facing trauma and PTSD. What will their futures be like if we turn their backs on them now?” JRS works in Latin America with families fleeing violence, gangs and poverty. Some lawmakers are “very sympathetic and understand this,” Rosenhauer said, “and others are not so much.”

“It’s not a good idea to cut off aid,” said William Canny, executive director of the U.S. bishops’ Migration and Refugee Services office. Citing aid to El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras for job training, agriculture and other initiatives, “they are not things we want to cut off at this time,” he added.

Catholic teaching holds that “people have a right to migrate and the right to seek asylum. People also have a right to stay,” Canny said, adding, “We’d like them to stay. We’d like them to be able to stay where they are,” but if conditions are that bad where they live, offering “a bare human existence, then they have a right to migrate, for themselves and their children.”

Most of the aid in question doesn’t go directly to the governments themselves. Catholic Relief Services receives $38 million from the U.S. government for education and job programs in the three countries, according to Rick Jones, an El Salvador-based youth and migration policy adviser for CRS.

If the aid cutoff goes through, Jones told The Associated Press, “it will be sending the message, ‘Help is not on the way … and you’re going to be left on your own,'” Jones said. “And basically people left on their own are going to be more desperate and more people are going to leave.”

CRS president and CEO Sean Callahan, in an April 1 statement, opposed the yanking of aid.

“With bipartisan support, targeted U.S. assistance has improved prosperity for the poor and vulnerable in Central America. Such programs, implemented by agencies like CRS, have reduced poverty and food insecurity and helped address the underlying causes of violence and migration,” Callahan said. “Redirecting these funds will undermine long-term U.S. policy goals, lay waste to key progress gained, and exacerbate migration to our border.”

The dynamics of Latin American immigration have changed, according Adam Isacson, director for defense oversight at the Washington Office on Latin America.

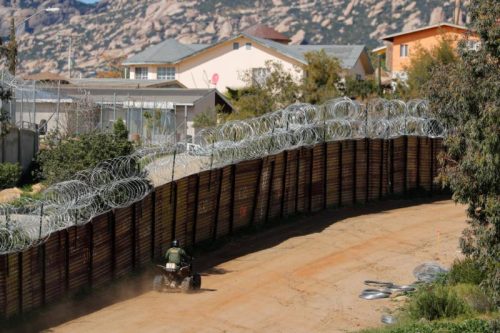

At immigration’s peak 20 years ago, “the (immigrant) population was almost entirely adults and almost entirely Mexican,” Isacson told CNS. The numbers started dropping in 2006, a trend that continued through 2011. Isacson attributed the drop to beefed-up border security, the installation of fencing at some parts of the 1,954-mile border, improvement in the Mexican economy and “Mexicans not bothering to come anymore.”

A slight uptick was registered in 2012, and “that’s when we first started hearing about children and families” making the trek to the United States, he said. Those numbers spiked in 2014, making headlines for about six months, he added.

Today, instead of single Mexican men crossing the border and hoping to evade capture, Isacson said, youths and families cross hoping to be caught so they can claim asylum.

On April 5, Trump called on Congress to “get rid of the whole asylum system.” So many border-crossers have claimed asylum that Customs and Border Patrol personnel are now outfitting them with ankle bracelets and court dates in a location closer to their stated destination because there are not enough beds in detention facilities, Isacson said.

More notably, those who claim asylum at the border have been forced to return to Mexico to wait for their hearing. “The backlog is so huge — 800,000 cases, 450 judges — people are being given hearing dates in 2022 or 2023,” Isacson said. “At some point, you have the right to work, legally, and in many cases it’s a happy story — for a few years.”

“By stating that he wants to get rid of the whole asylum system, the president is merely confirming publicly what his administration has been attempting to do for two years,” said Eleanor Acer, director of refugee protection program of the Washington-based organization Human Rights First, in an April 5 statement, calling Trump’s words “repugnant.”

Acer added, “President Trump and his hardline anti-immigration allies are systemically dismantling a system that is a lifeline for those fleeing violence and persecution. As one of the nation’s largest pro bono asylum providers, we know firsthand that asylum saves lives. It’s as simple as that.”

After Trump issued his threat to close the U.S.-Mexico border, news stories focused less on the fate of immigrants who could be stuck at the border and more on the fate of Mexican-grown avocados.

“I don’t know what the president would have hoped to accomplish with the closing of the border, if that’s drawing more attention this so-called border crisis,” said Victoria Neilson, managing attorney for the Defending Vulnerable Populations project of the Catholic Legal Immigration Network.

“The statistics have shown that are not more people at the border now than there were 20 years ago,” Neilson said. “It seems to be a manufactured crisis and potentially closing the border would be another manufactured crisis to keep this narrative in the headlines.”

Former Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson, who served in the Obama administration, has told reporters that “by anyone’s definition, by any measure, right now we have a crisis at our southern border.” At a March 27 news conference in El Paso, Texas, Customs and Border Patrol Commissioner Kevin McAleenan said the border is at a “breaking point.”

Others have shown skepticism — to the point of disdain — over Trump administration declarations of a border crisis.

“This administration has fueled only fear and more chaos,” said Ur Jaddou, director of DHS Watch, during an April 4 conference call with reporters on border issues. She added the United States had accepted only 525 refugees from all of Latin America in fiscal year 2018. “That is certainly not a robust refugee program that is an answer to the region’s humanitarian issues,” Jaddou said.

Ways to address the situation include “processing asylum-seekers but not with untrained CBP officers,” Jaddou said. “Their job is to enforce, not to consider humanitarian concerns.” (WOLA’s Isacson told CNS there are already Border Patrol agents “changing diapers and cooking burritos for folks they have to let in.”)

“There is already a cadre of trained asylum adjudicators. And more can be trained,” Jaddou added. “There is money for this. The last appropriation bill appropriated money for this, and it should be appropriated.”

The moves struck CLINIC’s Neilson as counterproductive.

“As a rational person, it does not seem at all logical to me if people are fleeing because of the government’s inability in the home country to stop widespread violence de facto formation of local government by organized gangs,” she said. “It seems pretty obvious that cutting off aid to those struggling governments will just lead to more violence and lead to more people fleeing the country, which does not seem like a policy choice that is going to lead to fewer people leave. It’s a policy choice that’s going to lead to more people leaving.”

The Sisters of Mercy of the Americas March 30 announced two separate delegations would visit the Texas-Mexico border — with one going to El Paso and across to Ciudda Juarez, Mexico, and the other to McAllen, Texas, in the Diocese of Brownsville — to investigate migrant ministries and border conditions.

The Ignatian Solidarity Network launched a message campaign asking the State Department to “reject President Trump’s call to end foreign aid to these Central American countries.

Instead of using foreign aid to bully other countries,” said Ted Penton, a Jesuit transitional deacon, in an April 3 statement, “they should commit to a form of diplomacy that engages stakeholders in a way that recognizes our shared interests and the need for long-term, creative solutions.”

In his own April 3 statement on the aid cutoff, Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin of Newark, New Jersey, said: “I continue to be amazed that some still do not understand what forces people to leave their home country. Most are escaping extreme violence and poverty. The decision to leave one’s home does not come easily or without sacrifice. Who would think that the best way to solve the problem of extreme poverty is to cut off humanitarian aid?”